Ai Weiwei (born 28 August 1957 in Beijing) is a Chinese Contemporary artist and activist.

His father side’s original surname is 蔣Jiang. Ai collaborated with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron as the artistic consultant on the Beijing National Stadium for the 2008 Olympics. As a political activist, he has been highly and openly critical of the Chinese Government’s stance on democracy and human rights. He has investigated government corruption and cover-ups, in particular the Sichuan schools corruption scandal following the collapse of so-called “tofu-dreg schools” in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. In 2011, following his arrest at Beijing Capital International Airport on 3 April, he was held for 81 days without any official charges being filed; officials alluded to their allegations of “economic crimes”.

Content

Ai Weiwei biography

Ai Weiwei, Wade-Giles romanization Ai Wei-wei (born May 18, 1957, Beijing, China) Chinese artist and activist who produced a multifaceted array of creative work, including sculptural installations, architectural projects, photographs, and videos. While Ai was lauded internationally, the frequently provocative and subversive dimension of his art, as well as his political outspokenness, triggered various forms of repression from Chinese authorities.

Ai Weiwei’s father was Ai Qing, one of China’s most renowned poets. Shortly after Weiwei was born, communist officials accused Ai Qing of being a rightist, and the family was exiled to remote locales—first to the northeastern province of Heilongjiang and then to the northwestern autonomous region of Xinjiang—before being allowed to return to Beijing in 1976, at the end of the Cultural Revolution. As a youth, Weiwei had become interested in art, and in 1978 he enrolled at the Beijing Film Academy, though he found more creative and intellectual stimulation as part of a collective of avant-garde artists called Xingxing (“Stars”). Eager to escape the restrictions of Chinese society, he moved to the United States in 1981. Settling in New York City, he attended Parsons School of Design (part of what is now the New School) and actively engaged in the city’s fertile subculture of artists and bohemians.

Although Ai initially focused on painting, he soon turned to sculpture, inspired by the ready-made works of the French artist Marcel Duchamp and the German sculptor Joseph Beuys. Among his early creations exhibited at a solo show in New York City in 1988 were a wire hanger bent into the shape of Duchamp’s profile and a violin with a shovel handle in place of its neck. There was little market for Ai’s work, however, and in 1993, when his father fell ill, he returned to Beijing. Exploring the fraught relationship of an increasingly modernized China to its cultural heritage, Ai began creating works that irrevocably transformed centuries-old Chinese artifacts—for instance, a Han dynasty urn onto which he painted the Coca-Cola logo (1994) and pieces of Ming- and Qing-era furniture broken down and reassembled into various nonfunctional configurations.

Between 1994 and 1997 Ai collaborated on three books that promoted avant-garde Chinese art; they were published outside official government channels and became signposts for China’s underground art community. His profile increased in 2000 when he cocurated an exhibition of deliberately outrageous art as an alternative to that year’s Shanghai Biennale. After building his own studio complex on the edge of Beijing in 1999, Ai turned toward architecture, and four years later he founded the design firm FAKE to realize his projects, which emphasized simplicity through the use of commonplace materials. An architectural notion of space later informed Ai’s Fairytale (2007), a conceptual project that involved transporting 1,001 ordinary Chinese citizens to Kassel, Germany, to explore the city for the duration of its Documenta art festival.

In 2005 Ai was invited to write a blog for the Chinese Web portal Sina. Although he initially used the blog as a means of documenting the mundane aspects of his life, he soon found it a suitable forum for his often blunt criticism of the Chinese government. Through the blog, Ai publicly disavowed his role in helping to conceive the design of the National Stadium (popularly dubbed the Bird’s Nest) in Beijing, claiming that the 2008 Olympic Games for which the structure had been built were tainted by official corruption and amounted to government propaganda. Furthermore, nearly a year after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake—in which shoddy construction was suspected to have been responsible for the deaths of thousands of children in collapsed public schools—Ai lambasted officials for not having released details on the fatalities and mobilized his growing readership to investigate. The blog was soon shut down, and Ai was placed under surveillance, though he refused to curtail his activities. (He transferred his online presence to Twitter.) Later in 2009 he was assaulted by police in Chengdu, where he was supporting a kindred activist on trial. Among the artworks that resulted from Ai’s “citizen investigation” was Remembering (2009), an installation in Munich in which 9,000 coloured backpacks were arranged on a wall to form a quote, in Chinese, from an earthquake victim’s mother.

Ai earned praise in 2010 for his installation, at the Tate Modern in London, of 100 million hand-painted porcelain “sunflower seeds,” which were produced by some 1,600 Chinese artisans. Until the exhibit was roped off because of a feared health hazard, Ai had encouraged visitors to walk upon the seeds, considering the fragile sculptures a metaphor for the downtrodden Chinese populace. In late 2010 Ai was notified that a studio complex in Shanghai that he had recently built at the invitation of the city’s mayor was scheduled to be razed. Though local authorities cited Ai’s failure to obtain a required permit as the reason for the demolition, Ai himself speculated that two documentary films he had made that suggested injustices on the part of Shanghai’s government may have been the underlying impetus. Ai was briefly placed under house arrest to prevent him from attending a party at the complex in November, and the site was demolished two months later. Also in November Ai launched another citizen investigation following a deadly fire in a Shanghai high-rise apartment building.

In April 2011 Ai was detained for alleged “economic crimes”—it was later revealed that he was accused of tax evasion—in what was seen as part of a widespread crackdown on dissent. He was released on bail more than two months later, with Chinese state media reporting that he had confessed to the charges against him. In November, however, Ai was levied with a tax bill of 15 million yuan ($2.4 million). He contested the bill with the aid of private donations, but his final appeal was denied in court in September 2012, and shortly thereafter he announced that FAKE’s business license had been revoked. The international media coverage of the incidents brought further attention to Ai’s art. In May 2011, while he was still in detention, his public installation Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads, which featured bronze sculptures inspired by the Chinese zodiac, was unveiled in New York City and London. The work had been created for the São Paulo Biennial in 2010.

A major career retrospective, Ai Weiwei: According to What?, which had originated in Tokyo in 2009, debuted at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. The documentaries Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry (2012) and Ai Weiwei: The Fake Case (2013) depicted the artist’s achievements and vicissitudes.

Ai Weiwei art

Ai Weiwei Art Career

Chairs Art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times: “From a Western perspective, Mr. Ai’s career fits a familiar profile. We tend to like our contemporary Chinese artists to come across as aesthetic tradition-busters. In this regard Mr. Ai has not disappointed. In the 1990s he painted Coca-Cola logos on ancient Chinese pots and broke up classical Chinese furniture.”

“But gradually such Duchampian moves have given way to large-scale, socially critical projects. For a conceptual piece called “Fairytale” at the 200 7Documenta in Kassel, Germany, he placed 1,001 antique Chinese chairs, available for use, throughout the exhibition. He built an outdoor structure from 1,001 doors salvaged from Ming and Qing houses that had been eliminated by rampant development in Chinese cities. Through the Internet he recruited 1,001 Chinese citizen-volunteers to come to Kassel to live for the duration of the show.”

“In short, he brought a sense of China that was at once inviting, puzzling and pathetic. The chairs were nice to sit in. It was hard to know what to make of the mini-army of temporary residents, who seemed equally uncertain of why they were there. The structure built from old doors finally just collapsed. Over all, “Fairytale” was not a winning picture of his homeland.”

“As an international celebrity he was still a feather in China’s cap at a time when the country was making an all-out effort to become a major cultural presence prior to the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. With this in mind the Chinese government asked Mr. Ai to collaborate with the Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron on the design for the Olympic stadium, known the Bird’s Nest. He did so. The result was a triumph.”

“Through all of this, his own work, which came to include sculpture, photography, performance and architecture, fit no definable mode. It was his personal presence as impresario, entrepreneur and social commentator that gave it unity. And increasingly it was the critical commentary that stood out, became a form of performance art, carefully choreographed in all its moves. And those moves were toward ever greater risk.”

“His attacks on political authority grew sharper, more persistent, more amplified. The noble Confucian model of the morally grounded intellectual speaking truth to power in a single dramatic confrontation was called on so often as to become, seemingly by intention, an unnoble and relentless insistence. And as a result, whatever immunity from reprisal he might once have enjoyed was soon gone.”

Ai Weiwei’s Art

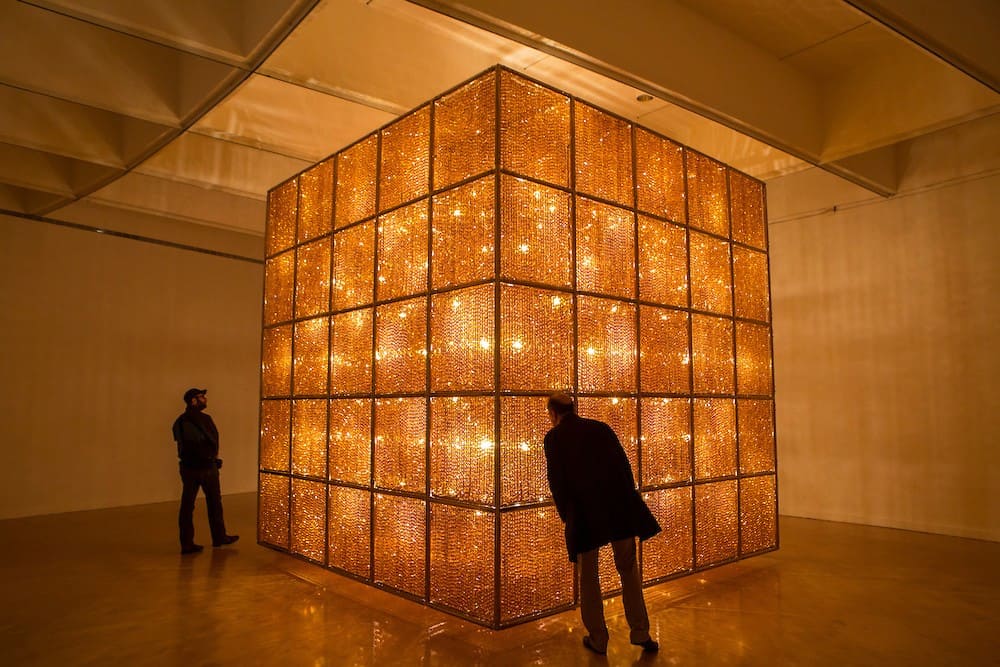

Cube Light Mr Ai is famous in artistic circles for performance pieces that explored the dizzying change of contemporary China and for irreverent, avant garde works such as a photo series that shows him giving the middle finger to landmarks such as Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City in Beijing, the White House in Washington, and the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Nicholas Logsdail, director of the Lisson Gallery in London, which did an exhibition of his work, wrote in The Guardian: “In my opinion, Ai Weiwei is one of the major artists of the early 21st century… He’s not just the most important Chinese artist of his generation but a truly international figure… His work is a very interesting blend of traditionalism and liberalism, with a revolutionary bent. He has an outspoken nature, which is what has got him into trouble, but my reading is that his primary impulse is less to overturn society than to improve it. He is unwilling to keep quiet in the face of ignorance and prejudice and he speaks out against injustice wherever he finds it.”

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, “In one of his early acclaimed works, a series of three photographs called Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, he dispassionately shatters a priceless ancient Chinese vase, striking a theme—destruction and recreation—that runs through much of his art. Other works employ Ming and Qin period urns, furniture and architecture, assembled into haunting new creations, or painted over, Warhol-style, with the Coca-Cola logo, or speared by wooden beams.

Ai served as the artistic consultant on the Beijing National Stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Ai now regrets participating in the”Bird’s Nest” project. “The Beijing Olympics have oppressed the life of the general public with the latest technologies and a security apparatus of 700,000 guards. It was merely a stage for a political party [the Chinese Communist Party] to advertise its glory to the world,” he said. “I became disenchanted [over the project] because I realized I was used by the government to spread their patriotic education. Since the Olympics, I haven’t looked at [the stadium],” he said.

In Munich, Ai exhibited a work called So Sorry addressed to the government’s near-silence on schoolchildren who died in the Sichuan Earthquake. Describing by the New York Times as his—most arresting work of art to date— it comprises 9,000 children’s backpacks, covering one exterior wall of the Haus der Kunst museum . Against a blue background, colored bags form the Chinese characters for the message, ‘she lived happily on this earth for seven years,” a quotation from a mother of one earthquake victim.

Ai and Art with the Naked Body

The Chinese poet Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning, “Ai is an energetic and prolific concept artist. The word “concept” includes for him his own concept of society, of the world in general. In his 10 years as an illegal alien in New York, he spent a lot of time in museums and galleries. He always walked everywhere, so he would pass 40 to 50 blocks walking to the Museum of Modern Art or the Metropolitan Museum, for example. He often talked about his enthusiasm for Andy Warhol. Ai may be one of the very few people who have thoroughly digested and understood Warhol. But he goes further than the pop-art pioneer, because he uses concepts to challenge state power.

Ai remains preoccupied with the naked body. After he returned to the mainland, in 1993, his nude performance pieces gradually acquired levels of metaphor and satire. There is a famous photograph from Tiananmen Square, taken on June 4, 1994, the fifth anniversary of the massacre. With the skills he had learned in New York, Ai and his girlfriend, Lu Qing, were able to move through rows of police and plain-clothes detectives, to the middle of the square, opposite the portrait of Mao. Lu, who became Ai’s wife, positioned herself in front of a fence, with Mao’s face between her and another woman. Ai’s camera captured the moment she raised her skirt and revealed her underwear, with one of her feet drawn up, as in a dancing pose. The challenge to the authorities is obvious when you see the picture but there’s hardly anything illegal in it. The photo was published in underground art publications throughout the rest of the 90s.

After 2000, in the age of the digital camera, Ai became more forthright when photographing his own body. His pictures became more vulgar, flouting aesthetic standards and feelings of shame. In September 2008, he took shots of his bulging belly and posted them on his blog. These images were meant to be shocking and make the observer reflect on ugliness. The burning cigarette in his navel certainly looked vulgar enough. But there was no hidden intention to be discerned behind the vulgarity. All you can see is a shameless ageing man, who has never changed the naughty ways that have always been natural to him.

The peak of Ai’s nude online presence was reached with a series of photos of himself alone or in a group, each with characteristic titles. In May 2009, Ai took five pictures. One of the pictures’ titles could be translated as “the grass mud horse blocking the centre”, another one as “flying high, don’t forget to hide the central authority”.

“Hiding” and “blocking the centre of power” are puns, because “hiding” and “blocking” sound like “party” in Chinese, and “the party centre” always means the Communist Party’s Central Committee. “Flying high, don’t forget the party centre” and “flying high, don’t forget to hide the central authority” sound exactly the same (tengfei bu wang dang zhongyang; “flying high” is a phrase often used in state propaganda to celebrate economic or political successes). The phrase “grass mud horse” is another pun, being phonetically similar to “f*** your mother”. Here, it could be seen that the Central Committee is being encouraged to do just that. The use of a “grass mud horse” toy to cover your privates thus becomes an obscenity aimed at the most serious and sacred body at the centre of state power.

Ai went further. He took pictures of more and more people together, all naked except for a grass mud horse. They were artists, internet users, lawyers and activists, and included Shanghai civil rights campaigner Feng Zhenghu. Ai’s creative talent and his inclination to nudity reinforced each other through the use of political metaphors.

Ai Weiwei’s One Tiger, Eight Breasts

Dust to Dust Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning, “On April 3, Ai was seized by security agents at Beijing airport (SEHK: 0694), as he was about to board a plane to Hong Kong. After he disappeared into incarceration, internet users, including government-paid agents (the “50-cent crew”) searched frantically for nude pictures of Ai. One series of images became widely known under the online moniker “One Tiger, Eight Breasts”. Many interpretations of these images have been offered. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

The classic interpretation of the group image runs like this: Ai sits in command at the centre. His manner is straightforward, but almost accidentally his hands cover the vital parts, which evokes an illusion to the Central Committee. Ai’s hands rest on his left knee, indicating a resolute leftist stance.

The long-haired young woman on the left of the picture sits with her legs crossed on a backless chair. She symbolises the intellectual, since she has her own position and posture, but she has no backing and cannot be relied on. She’s playing with her hair while her body is inclined towards the party centre, which means whatever intellectuals are playing at, they will always be dragged away by the government.

The woman on the right (Ye Haiyan, an activist from Wuhan, Hubei province) has a well-rounded figure and wears a jade pendant and a watch, so she’s the bourgeoisie; she has a position, which can be relied on. Her hands are kept at her right side, hinting at her rightist standpoint. In the composition of the whole picture, there is an obvious distance between the party centre and the bourgeoisie. They are on polite and formal terms. The figures of the bourgeoisie and the party centre can be seen in other pictures, with different postures, meaning they have secret dealings.

The short-haired woman in the centre, sharing a seat with Ai, doesn’t have her own position to sit on, so she must have been standing and smiling politely before she was pulled in and made to rest with the Central Committee. She is the media, kept in her place by the party. Finally, the girl at the back having to hide all the way behind the chairs is a migrant labourer and therefore in a classless position. It’s all in the eye of the beholder, whether you see moral turpitude, a romantic situation or a tableau of political hints. This picture continues the style of Ai’s other nude art projects. There is a natural and carefree attitude in the poses and expressions of the models. The pictures are not indecent – and the interpretation above does seem to be rather far-fetched, on the whole.

Story Behind Ai Weiwei’s One Tiger, Eight Breasts

One Ton of Tea The Chinese poet Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning,” The group picture was taken when Ye Haiyan (her name means “sea swallow”) visited Ai in his atelier last year. The other women were online fans. They had come to know about each other on Twitter. Ye was deeply impressed by Ai’s documentaries from the aftermath of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and also by his film on Yang Jia, who had broken into a police station and stabbed six policemen to death. Yang was sentenced to death but received a lot of public sympathy, pointing to widespread anger and frustration. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

After seeing those documentaries, Ye searched the web and learned about Ai’s art – chairs with three legs, modified ancient tables and coffins – and found pictures of Ai and his (male) artist companions in the nude. She was impressed by his approach and took her daughter to a gathering for earthquake victims, organised by Ai and his friends. Later, Ye went with a friend to Ai’s Beijing studio. The artist often invited visitors to take part in his performance pieces. When her friend suggested it, Ye agreed to do it.

“Apart from the photographer, there was no one else around,” Ye wrote in an internet posting, on April 20. “We took our clothes off there at the atelier. It was a serious occasion for us. We felt natural, as if we were wearing clothes, but if you’ve never had such an experience, maybe you can’t even face a human body, because you feel weak, or filthy. We were very proud when we had finished. Ai named it Open Encounter.” About the picture, she wrote: “I don’t think there is any allegory, it’s very simple, just about the human body; but I don’t reject any interpretations, you can try out how far your thoughts will take you.”

Ai’s nude projects may have some spiritual common ground with aspects of Zen and chivalry in ancient China. Some Zen monks liked to bare their chest and shed their clothes. Zen carries a tradition of seeking direct access to the heart and soul, stripping away anything else. “See the basic nature and attain Buddha-hood” is a known phrase. There is a certain theatrical aspect in Zen Buddhism, with abrupt language and actions. Irreverence is very important. The spontaneous and carefree attitude exhibited in Ai’s performances comes close to this clownish aspect of Zen. And the chivalrous tradition, originating about 2,000 years ago during the Han dynasty, stresses a few basic values, which I also see expressed in Ai’s championing of basic rights.

Who’s Afraid of Ai Weiwei Ai Weiwei’s Films

One Ton of Ebony Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning,” Who is afraid of Ai Weiwei” Ai has many names. “Wei” is a basic character, one of the 12 earthly branches used for time-keeping; commonly, “wei” means “not yet”. The family name Ai is also a simple character, a name Weiwei’s father, Ai Qing, chose for himself at the beginning of his artistic career. To confuse government-paid internet agents, Ai has used the Chinese characters for “ai” and “wei” in many combinations. The most common abbreviation in roman letters is aiww, as used for his Twitter account. Who is afraid of Ai Weiwei” Well, one thing is clear: Ai himself acted as if he feared nothing and no one. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

Ai does not just like to get naked by himself or with friends, he has also helped to lay bare “China”, from the Central Committee to regional administrations. His approach is different from the serious mien of the traditional dissident intellectual. He has his own brand of indignation, mixed with an easy humour, to face the violence of state power.

Ai knew prison was waiting for him, that he could even lose his life. “Who says I am not afraid? I am very much afraid, but if I stop and do nothing, it would feel even more terrible,” he told me in 2009, at the opening of an exhibition of his in Munich, Germany. Ai had a bandage on his head after having had emergency surgery as a result of a beating he’d received from police in Chengdu, Sichuan province.

Ai’s 40-odd collaborators have a strong team spirit. In 2009, artist Yang Licai, who worked at Ai’s studio, told Taiwan’s China Times: “Ai Weiwei is not just one man on a quest. There is a band of fellow Don Quixotes riding along with him, and behind every one of them is a very dedicated crew. And behind all of them are untold and unseen masses of people. They have no other common goal than to lead a decent life.”

Ai Weiwei’s film Disturbing the Peacea is a god example of his irreverent and aggressive filmmaking, especially when dealing with the police. The question of “respect” comes up in discussion of the film. Some audience asked whether he was disrespectful to the police and forcing the camera into people’s faces; others commented on the various ways the film camera might have intervened into the interactions captured on the screen, whether filmmaking spurred violence and confrontation at times, while repressing them at other times.

Ai Wei Wei’s Tate Gallery Instillation

Sunflower at the Tate The Tate Modern gallery in London hosted Ai’s huge installation “Sunflower Seeds” made up 100 million hand-crafted porcelain seeds placed on the floor in the cavernous Turbine Hall. The sunflower seeds exhibition was enthusiastically received by critics, but ran into controversy when visitors were barred from walking on them because of the ceramic dust thrown up.

On the piece,Salman Rushdie wrote in New York Times, “The great Turbine Hall at London’s Tate Modern, a former power station, is a notoriously difficult space for an artist to fill with authority. Its immensity can dwarf the imaginations of all but a select tribe of modern artists who understand the mysteries of scale. Last October the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei covered the floor with his “Sunflower Seeds”: 100 million tiny porcelain objects, each handmade by a master craftsman, no two identical. The installation was a carpet of life, multitudinous, inexplicable and, in the best Surrealist sense, strange. The seeds were intended to be walked on, but further strangeness followed. It was discovered that when trampled they gave off a fine dust that could damage the lungs. These symbolic representations of life could, it appeared, be dangerous to the living. The exhibition was cordoned off and visitors had to walk carefully around the perimeter.

The Chinese writer Ma Jian, author of Beijing Coma wrote in an article published by Project Syndicate: “China’s people, Ai’s installation seems to imply, are like the millions of seeds spread across the Tate’s gargantuan entrance hall. No one cares whether they are humiliated or crushed under foot (as the seeds were allowed to be at the exhibition’s opening). Unfortunately, Ai has become one of the seeds, his freedom crushed by the heel of an inhuman state. “

Ai Wei Wei’s New York Chinese Zodiac

Sunflower at the Tate In May 2011 an outdoor sculptural piece by Ai called “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads” was installed at the Pulitzer Fountain outside the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “To most New Yorkers the dozen large cast-bronze animal heads, corresponding to the signs Chinese zodiac, will be simply winsome, or maybe a little freaky. To anyone knowing the historical reference behind these images, they’ll be explosive.

“They are based on a set of similar sculptures that once adorned a fountain at the 18th-century imperial Summer Palace called Yuanming Yuan near Beijing. In 1860 French and British soldiers occupying China torched the palace and carried off the zodiac heads, an act which to this day evokes popular outrage in China as an example of colonialist humiliation and of everything hateful about the West.”

“Getting all the heads back—only some have been returned—has become an impassioned nationalist mission. When two were offered for sale at Christie’s in 2009 as part of the Yves Saint Laurent estate, there were protest demonstrations—almost never allowed in any other context—across China.”

Mark Singer wrote in The New Yorker: Ai’s first public art commission in New York is a reinterpretation of a seventeenth-century water clock—a dozen bronze animal heads representing figures of the Chinese zodiac, to be situated within the Pulitzer Fountain across from the Plaza Hotel. On a return visit to New York in 2008, Ai’s friend Larry Warsh arranged a meeting with Adrian Benepe, the Parks Commissioner. The particulars emerged in February, 2009, when Warsh showed up at the studio the morning that the artist’s son, Ai Lao, was born.

“For someone who has words for everything, he had no words,” Warsh recalled. “We went right away to the hospital, and he showed me the baby. That was very moving. I’m a big baby fan. Then we went back to the studio and started discussing public sculpture and what would make sense for New York City. An art historian was with us. An auction of the Yves Saint Laurent estate was taking place around the same time at Christie’s in Paris. The zodiac clock had been installed in the Old Summer Palace, in Beijing, which was looted by the French and British in 1860. Two of the animal heads eventually wound up with Saint Laurent. Since these had been stolen, there was a huge controversy. Anyway, as we sat in the studio, Weiwei had this “Aha!” moment. He would create full-size bronze derivations of all twelve of the animal heads.”

The temporary home of the animal heads, which had been cast in Chengdu, turned out to be a secured building in New Jersey on the grounds of an early-twentieth-century estate in deep horse country—an unheated stucco-and-fieldstone redoubt formerly occupied by a tennis court with a spectators—balcony, huge mullioned windows, and a couple of bowling alleys in the basement. The bronzes lay on their sides in six wooden crates, swaddled in several layers of bubble wrap. The wrapping of one was cut away to reveal a four-foot circular base and, atop a six-foot pole, a convincing and intimidating rooster, wide-eyed, with an erect cockscomb, highly detailed feathers and wattles, and a beak large enough to swallow a cat. A dozen cylindrical marble foundations lay nearby.

The plans for the official unveiling in New York City included a press conference with Mayor Bloomberg and luncheons and dinners in Ai’s honor, after which he and Warsh had mapped an itinerary that included museum visits in Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, Washington, D.C., and London. All that was certain at the moment, however, was that the zodiac figures would be installed in New York, with or without the artist’s presence.

Chinese Dissident Artist Ai Weiwei on Responding to the Syrian Refugee Crisis and His New Life in Berlin

In protest of the Danish government’s decision to seize asylum seekers’ assets, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei pulled out of two exhibitions in Copenhagen—at the ARoS Aarhus Art Museum and the Faurschou Foundation—two weeks ago. One week later, he posed on a beach as drowned Syrian infant, Alan Kurdi, a move which some have suggested steps outside the boundaries of artistic provocation. This week he begins filming a documentary about asylum seekers in Lesbos. Amidst these developments, Ai spoke to Artsy about responding to the Syrian refugee crisis, his new life in Berlin, and a pressing sense of urgency to do what he can to change the world while he still has time.

“The one thing I should give the Chinese government credit for is the fact that being unable to travel allowed me to focus on my work,” says Ai Weiwei with a wry smile. “Today I really miss that—my schedule is booked months in advance and it feels as though all I do is go from one place to the next. I’m not entirely sure how long I can keep this up.” There is, of course, an irony to this statement, which Ai acknowledges with a soft laugh. We are sitting next to a small arrangement of colorful Lego blocks at one of the long wooden trestle tables that inhabit the high, domed vaults comprising his impressive subterranean Berlin studio space. (Olafur Eliasson is a neighbor, albeit above ground.) A former brewery, the studio spans a vast, cavernous network of tunnels leading off in all directions. At one point we walk past a dark alcove containing what must be hundreds of wooden stools, not unlike those used in Ai’s iconic Grapes (2010) sculptures. The temptation to wander off and explore is overwhelming.

By now, most are familiar with the Chinese activist/artist’s story: When Ai was only one year old, his father, the poet Ai Qing, was exiled along with his family first to northeast and later to northwest China, where the family dwelt for a backbreaking 16 years, at one point living in a hole in the ground. Upon then-Chairman Mao Zedong’s death the family was able to return to Beijing, and Ai subsequently studied animation at the Beijing Film Academy, became a member of the original Chinese avant-garde, and spent 12 years in the U.S.—10 of those in New York, his home serving as a hub for visiting artists and musicians. He returned to Beijing in 1993, and it wasn’t long before his specially-constructed studio-house in the city’s Caochangdi district attracted other artists and galleries to the area.

Career highlights include collaborating with Herzog & de Meuron on Beijing’s National Stadium (before infamously sharing his disenchantment with the project as a vessel to promote the ruling party), and participating at Documenta 12 in 2007. When he was introduced to the internet in 2005, prolific blogging saw his fan base increase even more. However, it was his probing “Citizens’ Investigation” of the deaths of over 5000 schoolchildren in the wake of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that brought Ai global attention and sealed his difficult relationship with the authorities (including the shutting down of his blog and demolition of a newly constructed studio in Shanghai). In 2011, he was arrested without being officially charged for any crime and secretly detained for almost three months. By the time he emerged, he had become a global sensation. Last year, Ai finally received his passport and, with it, permission to travel again. After years of being under virtual house arrest, he was free. The media went into a fever pitch and by the end of 2015, it felt as though Ai was everywhere. And he was.

Media saturation is, of course, a dangerous game, the media being a fickle beast that can turn on you at any point, but one Ai has navigated fairly well to date. His prolific tweeting connects not only to his legions of fans, but relentlessly exposes inequality and corruption—he famously used it to document his surgery to treat a cerebral hemorrhage linked to being attacked by police in 2009. In spite of the often sobering issues he deals with, perhaps Ai has remained so prolific because he doesn’t take himself too seriously. He also has the rare ability to feel utterly sincere without being overly earnest. “They always say that time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself,” Andy Warhol once said. This seems particularly apt, given that Ai’s latest project deals with the refugee crisis (also the topic of his teaching for the next three years at the Berlin University of the Arts). He recently announced that he has established a studio on the Greek island of Lesbos, the landing point for many of the refugees coming into Europe and a site of intense, polarizing debate. It’s there that our conversation begins.

Anna Wallace-Thompson: Why Lesbos?

Ai Weiwei: I know what it’s like to be desperate, to lose everything you’re familiar with. For these people [in Syria], to lose everything—their very past and history—it’s a human tragedy, and I can’t think of a worse tragedy except for death. These people are simply trying to survive.

I was in Athens to talk about having a show there and Lesbos is extremely close, so I went there, only knowing that it was a connecting point for refugees coming into Europe. It’s such a beautiful island, and we were driving along, the sun was shining, there were tourists around. And then, in an instant, we saw a boat approach full of women and children. You see how desperate their situation is. People drown. Children drown. Nothing can prepare you for seeing all these people in their desperation.

Nobody who’s witnessed this, surely, can stand by and do nothing. By setting up a studio in Lesbos we can be right in the middle of it, and document what’s happening. It’s like a war zone there. This does not reflect the ideology and beliefs of the EU! The UN treaty on refugees is very clear: Anybody who seeks to be in another place due to political [persecution], war, or religious discrimination is a refugee and should be treated equally.

Do you worry that people will think you’re exploiting refugees for the sake of your art or your own gain?

People will always have opinions. I’m ready for anything as long as I can generate discussion on this issue. If I can use being in the spotlight to highlight what’s happening in Lesbos, then that’s a starting point.

A significant amount of your work deals with children—often as the innocent victims of the machinations of adults (even your son was put under surveillance). Was this interest amplified by having a child of your own?

I think this focus has become stronger after my son was born, yes, but also probably stems from my own childhood. Children are so incredibly vulnerable. They are subject to conditions that are forced upon them. They don’t understand the world: they’re not religious, they’re not divided. A child is a child, they’re all equal. They’re innocents. Women and children are always the first to be victimized and bear the brunt of war, violence and poverty. I hadn’t really thought of this as a special focus of mine, but now that you mention it, I realize the issue of children shakes me the most, because children are our future—we cannot see lives shortened or deprived of potential simply because we saw something wrong and hesitated to act. We have no excuse. If we’re not happy with the way things are, we better do something so we create a better world for our children. Otherwise parenthood is a joke.

In works such as Straight (2008-2012), which memorialized the children killed in the Sichuan earthquake, your outrage is palpable.

When the earthquake occurred, it kind of knocked me out, the idea that over 5000 children could disappear. I thought the very least I could do was find out who they are. What names did their parents give them? What were their birthdays? In which classroom did they lose their life? Which building and under what conditions? The only trace they have left on this earth is their name…a name that their parents poured all their hopes and love into. Humankind has a very short memory. Those children who suffocated in the garbage container were left because their parents had been forced to go and find work in the city. In the same town as those boys there were three or four children who committed suicide out of desperation—they had been left by their parents with nothing but a pail of corn to sustain themselves. Even an animal needs more than the bare minimum to survive—it needs love; it needs affection—and this is how we treat children!

Why did you choose to settle in Berlin?

I came to Berlin six years ago and felt this city was quite broken. It’s kind of like New York in the ’80s in the Lower East Side. It also has qualities of Beijing: It’s very loose, it doesn’t have a strong identity; it’s not like Paris or London in that sense. Berlin is a little…scruffy. I like that. I like that I can walk down the street and nobody pays me too much attention. Well, that’s started changing recently and now people want selfies and to shake hands. The Germans, well, they have a very firm grip; I think I’ve broken all the bones in my hand! This location also immediately interested me—I have a history of being underground. I’m comfortable with it. I also like being surrounded by this place’s history. The architecture is a work of art in itself.

You went back to China for two weeks in December. Are you afraid your passport could be revoked again if you go home?

The fear is always there because they may have reversed their decision on me, but China itself has not changed. For me, a free person is somebody who doesn’t have to be pushed out—it’s important to be able to go back when I want. However, if it happened once it can always happen again. They never officially acknowledged that what they did was wrong.

Did it ever feel overwhelming? Does the constant fighting make you tired?

I’m so tired. You realize the more you do the less you did. There’s so much more that can be done. And of course, you know, I’m not young any more, so how far can I stretch myself? There is a sense of urgency, as well as a sense of physical tiredness because there is so much to do and limited time and energy.

Do you ever worry the Ai Weiwei “brand” will become bigger than you can control?

People will always see what they want to see. I don’t really worry about what other people think. There’s so much more I want to be doing that I need to focus on. I think a person is only in danger of getting lost inside celebrity or the like if they are not solid in the definition of who they are. When you let the world tell you who you are or you try to prove yourself to it, that’s when you lose your way.

This is what’s so interesting about “Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei.” Warhol was in many ways an intensely private person. Your life is so public—how do you divide public and private?

I often say that I don’t differentiate the two, but that’s not true. The more you are exposed, the further within yourself you have to go to find a place that is all your own, where people can’t touch your innermost private self. Warhol is a great example. It was only after his death that people found out what his life was actually like. He used to serve people in the soup kitchen of a church every Christmas, for example, and his house was the opposite of his modern image, filled instead with antiques. None of it related to his “look.” He was deeply in his own, other world. If all you have is what’s on the surface, what’s left?

How conscious are you of your audience?

Very. I think of the specific location, and imagine how the works would look there—what kind of visual language will they convey? It’s a little bit like flirting—you have to get to know the space a little bit first. I like having shows in different locations and don’t like having a show twice in the same city. New locations mean new challenges.

After Lego refused to fill your bulk order, it was your audience that came together to donate pieces for you.

When Lego refused to fill our bulk order, it came as a surprise. Lego’s stance was that they have a policy not to get involved in anything potentially political. My argument is that water is not political, air is not political, freedom is not political—freedom is necessary for artists. We have no other way of life. So I vented my frustrations on Instagram and people began asking how they could donate Lego. I thought of setting up cars, they’re easy to move and you can park them anywhere, and suddenly we had 20 museums and institutions volunteering space for them. [It should be noted that Lego changed its bulk buying policy on January 12th, after the backlash it received from this.]

Is this the stuff that keeps you going?

Yes it is, and the internet is so important here because it’s a celebration of people. I think the internet is like a modern church. In a church, you worship something, the divine, but people on the internet worship individualism and freedom of speech.

What, ultimately, is “freedom”?

For me? Freedom is a vehicle that leads me to ever more difficult conditions. It brings me to areas that I would never even have imagined and it questions my existence.

—Anna Wallace-Thompson

Ai Weiwei facts

- Ai Weiwei’s wife, Lu Qing, is also an artist. While her husband’s work is a form of activism, hers is a form of reflection. Lu produces a single work annually, filling a bolt of silk 82 feet long with painted patterns.

- Ai Weiwei is an ambassador for Reporters Without Borders (RSF). His photographs will feature in RSF’s 2013 album “100 Photos for Press Freedom.” The latest issue was released on September 12, 2013, and was dedicated to the fight for free expression in China. Ai Weiwei’s work in this album chronicles his shadowing and surveillance by China’s secret police.

- Ai Weiwei is a heavy metal musician. His most recent album was titled “The Divine Comedy” and he has released two singles on his YouTube Channel. The video for the first single, “Dumbass” is a dramatization of the artist’s arbitrary 81-day detention in 2011. His second, “Laoma Tihua” is filmed in the style of a hidden camera and documents several instances of dubious police behaviour.

- Ai Weiwei is incredibly active on social media. You can find him on Twitter at @aiww. As the majority of his posts are delivered in his native Mandarin, a group of industrious artists have created a Twitter account that translates Ai Weiwei’s tweets into English (@aiwwenglish), which are then posted on a Tumblr account. You can also find him on Instagram at @aiww, for selfies, adorable pictures of his son, existential landscapes and more.

- Ai Weiwei’s name is a banned search term on Sina Weibo, China’s answer to Twitter.

- Ai Weiwei has very little involvement in the actual production of his works. He prefers to come up with the idea, make the main decisions, and have workers actualize his concepts. For this reason, his workers have referred to themselves as “hired assassins.”

- Ai Weiwei lived in New York City for 12 years, where he studied at Parsons School of Design and the Art Students League of New York. During this time, he also developed an interest in blackjack, making frequent trips to Atlantic City. Today, he is still regarded as a top tier professional blackjack player amongst gamblers.

- Ai Weiwei is a prolific documentary filmmaker. His most famous film is an investigation into the 2008 Sichuan earthquakes, titled Hua Lian Ba Er [Little Red Cheeks]. Another, Lao Ma Ti Hua [Disturbing the Peace] actually contains footage of his assault by Chinese police.

- Ai Weiwei had never used a computer before 2005. But from 2006-2009, he maintained a blog in which he heavily criticized the Chinese government. Although the blog has been taken down by Chinese authorities, its contents have been collected in a book, “Ai Weiwei’s Blog: Writings, Interviews, and Digital Rants, 2006-2009.”

- Ai Weiwei has addressed the erosion of China’s relationship with its own history in several works. As part of his conceptual piece Fairytale, the artist built a structure from 1001 Ming and Qing Dynasty doors that he collected following the demolition of these historic homes to make way for urban development. Another piece, Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads (currently on display in Toronto’s Nathan Phillips Square), explores China’s relationship to its national consciousness and cultural objects. This piece is due to be taken down on September 22, 2013 – so if you haven’t seen it yet, this is your last chance!

Ai Weiwei quotes

Without freedom of speech there is no modern world, just a barbaric one.

Art needs to stand for something.

Creativity is the power to reject the past, to change the status quo, and to seek new potential. Simply put, aside from using one’s imagination – perhaps more importantly – creativity is the power to act.

This exhibition has been an opportunity to reexamine past work and communicate with audiences from afar.

Dont retreat. Retweet!

I think it’s more important to show your work to the public.

Democracy, material wealth, and universal education are the soil upon which modernism exists.

Expressing oneself is like a drug. I’m so addicted to it.

I will never leave China, unless I am forced to. Because China is mine. I will not leave something that belongs to me in the hands of people I do not trust.

Politics is like air and water. And you know if there is bad politics. Everyone is polluted. Everyone is unhealthy. See the people walking on the street: how they act…

My work is always a ready-made… cultural, political, or social, and also it could be art – to make people re-look at what we have done, its original position, to create new possibilities.

Mass production is nothing new. Weren’t cathedrals built through mass production? The pyramids?… Paintings can be painted with the left hand, the right hand, someone else’s hand, or many people’s hands. The scale of production is irrelevant to its content.

We have to give our opinion; we have to say something, or we are a part of it. As an artist I am forced to say something.

I always want people to be confused, to be shocked or realize something later.

I’m a free man now, except I cannot leave China. You know, I have no desire to travel. I have so many things to do; I cannot finish them now.

In a society that restricts individual freedoms and violates human rights, anything that calls itself creative or independent is a pretence. It is impossible for a totalitarian society to create anything with passion and imagination.

Stupidity can win for a moment, but it can never really succeed because the nature of humans is to seek freedom. Rulers can delay that freedom, but they cannot stop it.