Andy Warhol (born Andrew Warhola; August 6, 1928 – February 22, 1987) was an American artist who was a leading figure in the visual art movement known as pop art. His works explore the relationship between artistic expression, celebrity culture, and advertisement that flourished by the 1960s.

After a successful career as a commercial illustrator, Warhol became a renowned and sometimes controversial artist. The Andy Warhol Museum in his native city, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, holds an extensive permanent collection of art and archives. It is the largest museum in the United States dedicated to a single artist.

Content

Andy Warhol biography

Childhood

Andy was the third child born to Czechoslovakian immigrant parents, Ondrej and Ulja (Julia) Warhola, in a working class neighborhood of Pittsburgh. He had two older brothers, John and Paul. As a child, Andy was smart and creative. His mother, a casual artist herself, encouraged his artistic urges by giving him his first camera at nine years old. Warhol was known to suffer from a nervous disorder that would frequently keep him at home, and, during these long periods, he would listen to the radio and collect pictures of movie stars around his bed. It was this exposure to current events at a young age that he later said shaped his obsession with pop culture and celebrities. When he was 14, his father passed away, leaving the family money to be specifically used towards higher learning for one of the boys. It was decided by the family that Andy would benefit the most from a college education.

Early Training

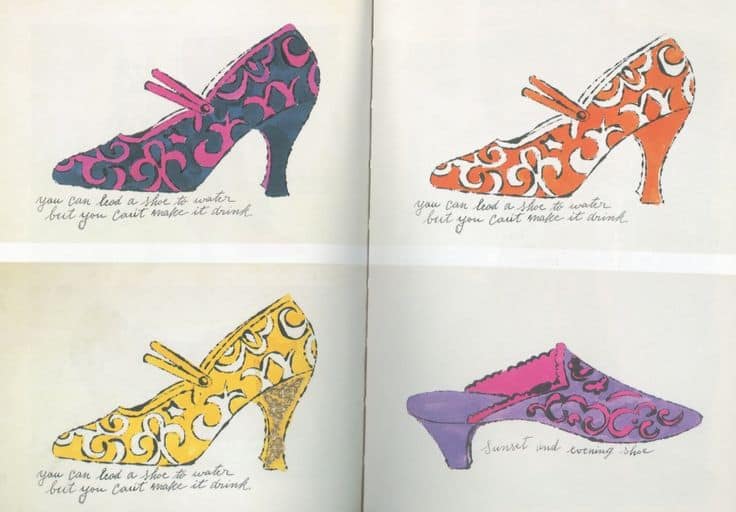

After graduating from high school at the age of 16, in 1945, Warhol attended Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), where he received formal training in pictorial design. Shortly after graduating, in 1949, he moved to New York City, where he worked as a commercial illustrator. His first project was for Glamour magazine for an article entitled, “Success is a Job in New York.” Throughout the 1950s Warhol continued his successful career in commercial illustration, working for several well-known magazines, such as Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and The New Yorker. He also produced advertising and window displays for local New York retailers. His work with I. Miller & Sons, for which his whimsical blotted line advertisements were particularly noticed, gained him some local notoriety, even winning several awards from the Art Director’s Club and the American Institute of Graphic Arts.

In the early 1950s, Andy shortened his name from Warhola to Warhol, and decided to strike out on his own as a serious artist. His experience and expertise in commercial art, combined with his immersion in American popular culture, influenced his most notable work. In 1952, he exhibited Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote in his first individual show at the Hugo Gallery in New York. While exhibiting work in several venues around New York City, he most notably exhibited at MoMA, where he participated in his first group show in 1956. Warhol took notice of new emerging artists, greatly admiring the work of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, which inspired him to expand his own artistic experimentation.

In 1960, Warhol began using advertisements and comic strips in his paintings. These works, examples of early Pop art, were characterized by more expressive and painterly styles that included clearly recognizable brushstrokes, and were loosely influenced by Abstract Expressionism. However, subsequent works, such his Brillo Boxes (1964), would mark a direct rebellion against Abstract Expressionism, by almost completely removing any evidence of the artist’s hand.

Mature Period

Andy Warhol worked across many media as a painter, printmaker, illustrator, filmmaker and writer. In September 1960, after moving to a townhouse at 1342 Lexington Avenue, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, he began his most prolific period. From having no dedicated studio space in his previous apartment, where he lived with his mother, he now had plenty of room to work. In 1962 he offered the Department of Real Estate $150 a month to rent a nearby obsolete fire house on East 87th Street. He was granted permission and used this space in conjunction with his Lexington Avenue space until 1964.

Continuing with the theme of advertisements and comic strips, his paintings throughout the early part of the 1960s were based primarily on illustrated images from printed media and graphic design. To create his large-scale graphic canvases, Warhol used an opaque projector to enlarge the images onto a large canvas on the wall. Then, working freehand, he would trace the image with paint directly onto the canvas without a pencil tracing underneath. As a result, Warhol’s works from early 1961 are generally more painterly.

Late in 1961, Warhol started on his Campbell’s Soup Can paintings. The series employed many different techniques, but most were created by projecting source images on to canvas, tracing them with a pencil, and then applying paint. In this way Warhol removed most signs of the artist’s hand.

In 1962 Warhol started to explore silkscreening. This stencil process involved transferring an image on to a porous screen, then applying paint or ink with a rubber squeegee. This marked another means of painting while removing traces of his hand; like the stencil processes he had used to create the Campbell’s Soup Can pictures, this also enabled him to repeat the motif multiple times across the same image, producing a serial image suggestive of mass production. Often, he would first set down a layer of colors which would compliment the stencilled image after it was applied.

His first silkscreened paintings were based on the front and back faces of dollar bills, and he went on to create several series of images of various consumer goods and commercial items using this method. He depicted shipping and handling labels, Coca-Cola bottles, coffee can labels, Brillo Soap box labels, matchbook covers, and cars. From autumn 1962 he also started to produce photo-silkscreen works, which involved transferring a photographic image on the porous silkscreens. His first was Baseball (1962), and those that followed often employed banal or shocking imagery derived from tabloid newspaper photographs of car crashes and civil rights riots, money and consumer household products.

In 1964 Warhol moved to 231 East 47th Street, calling it “The Factory.” Having achieved moderate success as an artist by this point, he was able to employ several assistants to help him execute his work. This marked a turning point in his career. Now, with the help of his assistants, he could more decisively remove his hand from the canvas and create repetitive, mass-produced images that would appear empty of meaning and beg the question, “What makes art, art?” This was an idea first introduced by Marcel Duchamp, whom Warhol admired.

Warhol had a lifelong fascination with Hollywood, demonstrated by his series of iconic images of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. He also expanded his medium into installations, most notably at the Stable Gallery in New York in 1964, replicating Brillo boxes in their actual size and then screenprinting their label designs onto blocks made of plywood.

Wanting to continue his exploration of different mediums, Warhol began experimenting with film in 1963. Two years later, after a trip to Paris for an exhibition of his work, he announced that he would be retiring from painting to focus exclusively on film. Although he never completely followed through with this intention, he did produce many films, most starring those whom he called the Warholstars, an eccentric and eclectic group of friends who frequented the Factory and were known for their unconventional lifestyle.

He created approximately 600 films between 1963 and 1976, films ranging in length from a few minutes to 24 hours. He also developed a project called The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, or EPI, in 1967. The EPI was a multi-media production combining The Velvet Underground rock band with projections of film, light and dance, culminating in a sensory experience of performance art. Warhol had also been self-publishing artist’s books since the 1950s, but his first mass produced book, Andy Warhol’s Index, was published in 1967. He later published several other books, and founded Interview Magazine with his friend Gerard Malanga in 1969. The magazine is dedicated to celebrities and is still in production today.

After an attempt on his life in 1968, by acquaintance and radical feminist, Valerie Solanas, he decided to distance himself from his unconventional entourage. This marked the end of the 1960s Factory scene. Warhol subsequently sought out companionship in New York high society, and throughout most of the 1970s his work consisted of commissioned portraits derived from printed Polaroid photographs. The most notable exception to this is his famous Mao series, which was done as a comment on President Richard Nixon’s visit to China. Lacking the glamour and commercial appeal of his earlier portraits, critics saw Warhol as prostituting his artistic talent, and viewed this later period as one of decline. However, Warhol saw financial success as an important goal. He had made the shift from commercial artist to business artist.

Late Years and Death

Ironically, in the late 1970s and 1980s, Warhol made a return to painting, and produced works that frequently verged on abstraction. His Oxidation Painting series, which were made by urinating on a canvas of copper paint, echoed the immediacy of the Abstract Expressionists and the rawness of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. By the 1980s, Warhol had regained much of his critical notoriety, due in part to his collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Francesco Clemente, two much younger and more cutting-edge artists. In the final years of Warhol’s life, he turned to religious subjects; his version of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper is particularly renowned. In these works, Warhol melded the sacred and the irreverent by juxtaposing enlarged logos of brands against images of Christ and his Apostles.

After suffering postoperative complications from a routine gall bladder procedure, Warhol died on February 22, 1987. He was buried in his hometown of Pittsburgh. His memorial service was held in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City and attended by more than 2,000 people.

Legacy

Andy Warhol was one of the most influential artists of the second half of the 20th century, creating some of the most recognizable images ever produced. Challenging the idealist visions and personal emotions conveyed by abstraction, Warhol embraced popular culture and commercial processes to produce work that appealed to the general public. He was one of the founding fathers of the Pop art movement, expanding the ideas of Duchamp by challenging the very definition of art. His artistic risks and constant experimentation with subjects and media made him a pioneer in almost all forms of visual art. His unconventional sense of style and his celebrity entourage helped him reach the mega-star status to which he aspired.

Warhol’s will dictated that his estate fund the Warhol Foundation for the advancement of the visual arts, which was subsequently created later that year. Through the joint efforts of the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, Dia Center for the Arts, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., the Warhol Museum was opened in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1994, housing a large collection of his work.

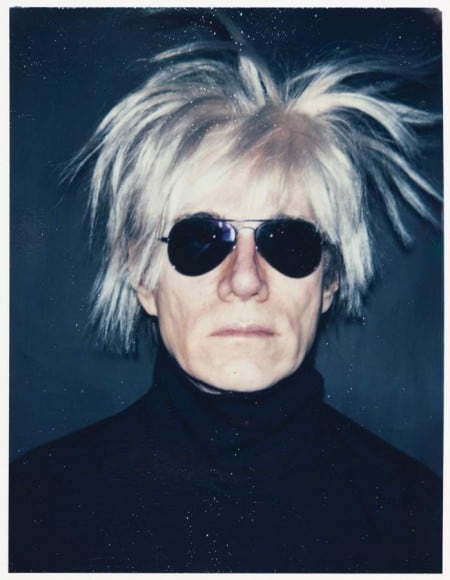

Andy Warhol art

The reigning king of pop art, Andy Warhol was an icon of of his age, an artist whose work and personality reflect the contours of the turbulent 1960s. Consumer products, sexual liberation, rock music, drug use, tragic death, and a heavy dose of shopping—the cultural phenomena that defined the decade are all on display in his art. Though he is best known for portraits of Elizabeth Taylor, deadpan paintings of Campbell’s soup cans, or polaroids of himself in a fright wig, Warhol’s legacy might be distilled in a single lyric by The Velvet Underground, the band that Warhol managed and included in his multimedia performances known as Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI) (1966-67): “I’ll be your mirror, reflect what you are, in case you don’t know.”

Warhol put his name and a peelable silk-screened banana on the cover of the band’s first album. He was the kind of artist who loved these double-moves, daring you to see the queer eroticism in his cut-and-dry imagery, promoting his name by pretending to efface it, and insisting on his individuality of expression while embracing the machine-like production of art. Though remarkably shy and reserved at times, Warhol found a way to make art of nearly everything he did, experimenting with a prolific variety of artistic media. From the early 1950s to his death in 1987, he was a conspicuous contributor to the realms of commercial illustration, graphic design, painting, printmaking, celebrity portraiture, performance art, and film. His artistic intuition and commercial success generated an extraordinary cult of celebrity around him, one that remains strong long after his death.

An Eye for Art and Pop Culture

Key to understanding Warhol and his enduring impact on the history of art is his appreciation of popular culture, the “pop” in pop art. He grew up as part of the working-class masses. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1928 to blue-collar Czechoslovakian immigrants, Andy was the youngest son of three. Developing a talent for art at a young age, he went on to study commercial art in college, earning a BFA in pictorial design from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1949.

After graduating, Warhol moved to New York City in order to find work as a commercial illustrator. His talents led to quick successes with magazine and newspaper ads, and his blotted, monotype-style work for fashion houses won widespread praise. A 1955 advertising campaign for the shoe manufacturer I. Miller & Sons, for instance, earned Warhol awards from the influential Art Directors Club, and opened many doors to new social contacts.

The New York Avant-Garde

By the mid-1950s, thanks to the ascendancy of abstract expressionism (aka “action painting”), New York had become the international capital of modern art. Warhol admired many of these artists, particularly Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg—whom he had come to know personally—and he was eager for his work to be considered as seriously as theirs. Warhol was interested in the Neo-Dada practices of Johns and Rauschenberg, but also in Richard Hamilton’s collages and Roy Lichtenstein’s Ben-Day dot paintings of comic strips. Blurring the line between fine art and popular culture, these artists inspired Warhol to make his first pop art paintings in 1960. He painted such early works as Water Heater (1961; New York, MoMA), and Saturday’s Popeye (1960; Mainz, Landesmus) in a loose style that winked at abstract expressionism, taking shapes and words from advertisements and painting them freehand on a white background.

Appropriation and Branding

To achieve these transfers of popular consumer imagery to his artwork more directly, Warhol soon turned to photographic screen-printing, a technique closer to serial factory production than painting with a brush. Silk-screened portraits of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, photo transfers of macabre headlines from tabloids, dollar bills, and Coca-Cola bottles entered Warhol’s compositions. These works led to the artist’s first solo show in November 1962 at the prominent Stable Gallery in the Upper East Side. While that exhibition established a recognizable medium and style for Warhol in the silkscreened portraits that he would make until the last years of his life, it was the 1964 show at Stable Gallery that made him a revolutionary.

The show consisted of over 400 sculptural works that were made to resemble common commercial items: Heinz Ketchup, Kellogg’s Cornflakes, Campbell’s Tomato Juice. The most canonical of these was a silkscreened wooden box of Brillo Soap Pads, a design Warhol had stolen from the abstract expressionist painter James Harvey. This appropriation—of products, celebrities, and even other artwork—demonstrates Warhol’s brilliance, cutting to the essential philosophical question of modernism: what is art (or what isn’t art)? After the Brillo box, Warhol’s response became, “art is what you can get away with.”

Filmmaking at “The Factory”

This conceptual redefinition of art was also embodied at the site of its production. Again equating art to consumer goods, Warhol called his foil-lined studio at 231 East 47th Street in Manhattan “The Factory,” a place where he could both supervise the assembly-line production of silkscreen portraits (on request for only $25,000) and host parties full of the “seedy glamor” he loved.

Fueled by amphetamines and his “Superstars”—hand-selected models, bohemians, and underground artists—Warhol began to experiment with filmmaking. Beginning in 1964, he made over 500 “Screen Tests,” short films in which Factory visitors simply sat and stared at the camera, often yielding an unexpected psychological intensity. By 1965, after his “Flowers” exhibition in Paris, Warhol announced that he would retire from painting in order to focus on making movies.

Filmmaking provided Warhol a vivid means of exploring personal issues, including his nihilism and homosexuality, and, through his approach to camera movement and narrative, of challenging established styles of cinema. Empire (1964) is a single, silent, slow-motion shot of the Empire State Building that runs for eight hours and five minutes. Even when he focuses on human figures, the camera doesn’t move to the main event, as in Blow Job (1964), in which viewers see a close-up of a young man’s face while the titular sex act he is purportedly receiving remains off-screen.

Warhol’s films, like his art, may remind their audiences of the subjectivity, even emptiness, of aesthetic experience. Therein lie sadness and beauty as strange bedfellows, an image Warhol himself would have appreciated. By the end of his career, Warhol was so universally accepted that he could exhibit work with a painter as conservative as Jamie Wyeth and one as bohemian as Jean-Michel Basquiat. In fact, his stock in the art world continues to rise—his work brought in a total of $653 million in auctions in 2014—indicating his fifteen minutes of fame are not likely to end anytime soon.

Andy Warhol facts

- He worked with many forms of media, including: painting, printmaking, photography, drawing, sculpture, film and music. He also started a magazine (called Interview Magazine) and he wrote several books.

- He called his studio The Factory and it became a famous meeting place for creative people and celebrities.

- Warhol was a hypochondriac and was scared of hospitals and doctors.

- In the 1960s he produced a series of paintings of iconic American images and objects, these included: Campbell’s Soup cans, dollar bills, Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley and Coca-Cola bottles.

- Andy Warhol was shot (and nearly died) on 3rd June 1968. The shooter was Valerie Solanas.

Andy Warhol quotes

If you want to know all about Andy Warhol just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.

How can you say one style is better than another? You ought to be able to be an Abstract Expressionist next week, or a Pop artist, or a realist, without feeling you’ve given up something.. I think that would be so great, to be able to change styles. And I think that’s what’s is going to happen, that’s going to be the whole new scene.

Everybody has a different idea of love. One girl I know said, “I knew he loved me when he didn’t come in my mouth.”

Don’t pay any attention to what they write about you. Just measure it in inches.

If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.

The pop artists did images that anybody walking down Broadway could recognize in a split second — comics, picnic tables, men’s trousers, celebrities, shower curtains, refrigerators, Coke bottles.

All the great modern things that the Abstract Expressionists tried not to notice at all.

Publicity is like eating peanuts. Once you start you can’t stop.

The interviewer should just tell me the words he wants me to say and I’ll repeat them after him. I think that would be so great because I’m so empty I just can’t think of anything to say.

I have Social Disease. I have to go out every night. I love going out every night. It’s so exciting.

The symptoms of Social disease: You want to go out every night because you’re afraid if you stay home you might miss something. You choose your friends according to whether or not they have a limousine…When you wake up in the morning, the first thing you do is read the society columns. If your name is actually mentioned your day is made. Publicity is the ultimate symptom of Social Disease.

I will go to the opening of anything, including a toilet seat.

Every time I go to Studio 54 I’m afraid I wont get in—maybe there will be somebody new at the door who won’t recognize me.

Uptown is for people who have already done something. Downtown is where they’re doing something now. I live uptown but I love downtown.

I like boring things.

I’d asked around 10 or 15 people for suggestions. Finally one lady friend asked the right question, “Well, what do you love most?” That’s how I started painting money.

Pop art is for everyone.

The artificial fascinates me, the bright and the shiny.

Do you know that the Campbell’s Soup Company has not sent me a single can of soup?

I love Los Angeles. I love Hollywood. They’re beautiful. Everybody’s plastic, but I love plastic. I want to be plastic.

Sex is more exciting on the screen and between the pages than between the sheets.

I am a deeply superficial person.

Success is when the checks don’t bounce.

I’d prefer to remain a mystery. I never like to give my background and, anyway, I make it all up different every time I’m asked. It’s not just that it’s part of my image not to tell everything, it’s just that I forget what I said the day before, and I have to make it all up over again.

Living in New York City gives people real incentives to want things that nobody else wants.

The most exciting thing is not doing it. If you fall in love with someone and never do it, it’s much more exciting.

In the future everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.

An artist is somebody who produces things that people don’t need to have.

References and useful Resources