Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez, known as Diego Rivera (December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a prominent Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the Mexican Mural Movement in Mexican art. Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted murals among others in Mexico City, Chapingo, Cuernavaca, San Francisco, Detroit, and New York City.

In 1931, a retrospective exhibition of his works was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Rivera had a volatile marriage with fellow Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

Content

Diego Rivera biography

Diego Rivera was one of Mexico’s most famous painters. He rebelled against the traditional school of painting and developed a style that combined historical, social, and political ideas. His great body of work reflects cultural changes taking place in Mexico and around the world during the turbulent twentieth century.

The young artist

Diego Maria Rivera and his twin brother Carlos were born in Guanajuato, Guanajuato State, Mexico, on December 8, 1886. Less than two years later his twin died. Diego’s parents were Diego Rivera and Maria Barrientos de Rivera. His father worked as a teacher, an editor for a newspaper, and a health inspector. His mother was a doctor. Diego began drawing when he was only three years old. His father soon built him a studio with canvas-covered walls and art supplies to keep the young artist from drawing on the walls and furniture in the house. As a child, Rivera was interested in trains and machines and was nicknamed “the engineer.” The Rivera family moved to Mexico City, Mexico, in 1892.

In 1897 Diego began studying painting at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico City. His instructors included Andrés Ríos Félix Para (1845–1919), Santiago Rebull (1829–1902), and José María Velasco (1840–1912). Para showed Rivera Mexican art that was different from the European art that he was used to. Rebull taught him that a good drawing was the basis of a good painting. Velasco taught Rivera how to produce three-dimensional effects. He was also influenced by the work of José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913), who produced scenes of everyday Mexican life engraved on metal.

In 1902 Rivera was expelled from the academy for leading a student protest when Porfirio Díaz (1830–1915) was reelected president of Mexico. Under Díaz’s leadership, those who disagreed with government policies faced harassment, imprisonment, and even death. Many of Mexico’s citizens lived in poverty, and there were no laws to protect the rights of workers. After Rivera was expelled, he traveled throughout Mexico painting and drawing.

Art in Europe

Although Rivera continued to work on his art in Mexico, he dreamed of studying in Europe. Finally, Teodora A. Dehesa, the governor of Veracruz, Mexico, who was known for funding artists, heard about Rivera’s talent and agreed to pay for his studies in Europe. In 1907 Rivera went to Madrid, Spain, and worked in the studio of Eduardo Chicharro. Then in 1909 he moved to Paris, France. In Paris he was influenced by impressionist painters, particularly Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919). Later he worked in a postimpressionist style inspired by Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Georges Seurat (1859–1891), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Raoul Dufy (1877–1953), and Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920).

As Rivera continued his travels in Europe, he experimented more with his techniques and styles of painting. The series of works he produced between 1913 and 1917 are cubist (a type of abstract art usually based on shapes or objects rather than pictures or scenes) in style. Some of the pieces have Mexican themes, such as the Guerrillero (1915). By 1918 he was producing pencil sketches of the highest quality, an example of which is his self-portrait. He continued his studies in Europe, traveling throughout Italy learning techniques of fresco (in which paint is applied to wet plaster) and mural painting before returning to Mexico in 1921.

Murals and frescoes

Rivera believed that all people (not just people who could buy art or go to museums) should be able to view the art that he was creating. He began painting large murals on walls in public buildings. Rivera’s first mural, the Creation (1922), in the Bolívar Amphitheater at the University of Mexico, was the first important mural of the twentieth century. The mural was painted using the encaustic method (a process where a color mixed with other materials is heated after it is applied). Rivera had a great sense of color and an enormous talent for structuring his works. In his later works he used historical, social, and political themes to show the history and the life of the Mexican people.

Between 1923 and 1926 Rivera created frescoes in the Ministry of Education Building in Mexico City. The frescoes in the Auditorium of the National School of Agriculture in Chapingo (1927) are considered his masterpiece. The oneness of the work and the quality of each of the different parts, particularly the feminine nudes, show off the height of his creative power. The general theme of the frescoes is human biological and social development. The murals in the Palace of Cortés in Cuernavaca (1929-1930) depict the fight against the Spanish conquerors.

Marriage, art, and controversy in the United States

In 1929 Rivera married the artist Frida Kahlo (1907–1954). The couple traveled in the United States, where Rivera produced many works of art, between 1930 and 1933. In San Francisco he painted murals for the Stock Exchange Luncheon Club and the California School of Fine Arts. Two years later he had an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. One of his most important works is the fresco in the Detroit Institute of Arts (1933), which depicts industrial life in the United States. Rivera returned to New York and began painting a mural for Rockefeller Center (1933). He was forced to stop work on the mural because it included a picture of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), the founder of the Russian Communist Party and the first leader of the Soviet Union. Many people in the United States disagreed with communism (a political and economic system in which property and goods are owned by the government and are supposed to be given to people based on their need) and Lenin and the mural was later destroyed. Rivera was a member of the Mexican Communist Party and many of his works included representations of his political beliefs. In New York Rivera also did a series of frescoes on movable panels depicting a portrait of America for the Independent Labor Institute before returning to Mexico in 1933.

Back to Mexico

After Rivera and Kahlo returned to Mexico, he painted a mural for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City (1934). This was a copy of the project that he had started in Rockefeller Center. In 1935 Rivera completed frescoes, which he had left unfinished in 1930, on the stairway in the National Palace. The frescoes show the history of Mexico from pre-Columbian times to the present and end with an image representing Karl Marx (1818–1883), the German philosopher and economist whose ideas became known as Marxism. These frescoes show Rivera’s political beliefs and his support of Marxism. The four movable panels he worked on for the Hotel Reforma (1936) were removed from the building because they depicted a representation of his views against Mexican political figures. During this period he painted portraits of Lupe Marín and Ruth Rivera and two easel paintings, Dancing Girl in Repose and the Dance of the Earth.

In 1940 Rivera returned to San Francisco to paint a mural for a junior college on the general theme of culture in the future. Rivera believed that the culture of the future would be a combination of the artistic genius of South America and the industrial genius of North America. His two murals in the National Institute of Cardiology in Mexico City (1944) show the development of cardiology (the study of the heart) and include portraits of the outstanding physicians in that field. In 1947 he painted a mural for the Hotel del Prado, A Dream in the Alameda.

A celebration of fifty years of art

In 1951 an exhibition honoring fifty years of Rivera’s art took place in the Palace of Fine Arts. His last works were mosaics for the stadium of the National University and for the Insurgents’ Theater, and a fresco in the Social Security Hospital No. 1. Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954. Diego Rivera died in Mexico City on November 25, 1957.

Diego Rivera art

Widely regarded as the most influential Mexican artist of the twentieth century, Diego Rivera was truly a larger-than-life figure who spent significant periods of his career in Europe and the U.S., in addition to his native Mexico. Together with David Alfaro Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco, Rivera was among the leading members and founders of the Mexican Muralist movement. Deploying a style informed by disparate sources such as European modern masters and Mexico’s pre-Columbian heritage, and executed in the technique of Italian fresco painting, Rivera handled major themes appropriate to the scale of his chosen art form: social inequality; the relationship of nature, industry, and technology; and the history and fate of Mexico. More than half a century after his death, Rivera is still among the most revered figures in Mexico, celebrated for both his role in the country’s artistic renaissance and re-invigoration of the mural genre as well as for his outsized persona.

Key Ideas

Rivera made the painting of murals his primary method, appreciating the large scale and public accessibility—the opposite of what he regarded as the elitist character of paintings in galleries and museums. Rivera used the walls of universities and other public buildings throughout Mexico and the United States as his canvas, creating an extraordinary body of work that revived interest in the mural as an art form and helped reinvent the concept of public art in the U.S. by paving the way for the Federal Art Program of the 1930s.

Mexican culture and history constituted the major themes and influence on Rivera’s art. Rivera, who amassed an enormous collection of pre-Columbian artifacts, created panoramic portrayals of Mexican history and daily life, from its Mayan beginnings up to the Mexican Revolution and post-Revolutionary present, in a style largely indebted to pre-Columbian culture.

A lifelong Marxist who belonged to the Mexican Communist Party and had important ties to the Soviet Union, Rivera is an exemplar of the socially committed artist. His art expressed his outspoken commitment to left-wing political causes, depicting such subjects as the Mexican peasantry, American workers, and revolutionary figures like Emiliano Zapata and Lenin. At times, his outspoken, uncompromising leftist politics collided with the wishes of wealthy patrons and aroused significant controversy that emanated inside and outside the art world.

Most Important Art

Zapatista Landscape –The Guerrilla (1915)

Artwork description & Analysis: In this work, painted during Rivera’s sojourn in Paris, the artist deployed Cubism—a style he once characterized as a “revolutionary movement”—to depict the Mexican revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata, here seen with attributes such as a rifle, bandolier, hat, and sarape. The work’s collage-like approach is suggestive of the Synthetic rather than Analytic phase of Cubism. Executed at the height of the Mexican Revolution, the painting—later described by its creator as “probably the most faithful expression of the Mexican mood that I have ever achieved”—manifests the increasing politicization of Rivera’s work.

Oil on canvas – Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City

Motherhood –Angelina and the Child (1916)

Artwork description & Analysis: Motherhood is a modernizing, Cubist treatment on a perennial art historical theme: the Madonna and Child. In this painting, Angelina Beloff, Rivera’s common-law wife for twelve years, holds their newborn son, Diego, who died of influenza just months after his birth. The painting beautifully illustrates Rivera’s unique approach to Cubism, which rejected the somber, monochromatic palette deployed by artists such as Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque in favor of vivid colors more reminiscent of those used by Italian Futurist artists like Gino Severini or Giacomo Balla.

Oil on canvas – Museo de Arte Alvar y Carmen T. de Carrillo Gil, Mexico

Creation (1922–23)

His first commission from Mexican Minister of Education Jose Vasconcelos, Creation is the first of Rivera’s many murals and a touchstone for Mexican Muralism. Treating, in the artist’s words, “the origins of the sciences and the arts, a kind of condensed version of human history”—the work is a complex allegorical composition, combining Mexican, Judeo-Christian, and Hellenic motifs. It depicts a number of allegorical figures—among them Faith, Hope, Charity, Education, and Science—all seemingly represented with unmistakably Mexican features. The figure of Song was modeled on Guadalupe Marin, who later became Rivera’s second wife. Through such features of the work as the use of gold leaf and the monumental, elongated figures, the mural reflects the importance of Italian and Byzantine art for Rivera’s development.

Fresco in encaustic with gold leaf – Museo de San Idelfonso, Mexico City

Portrait of Lupe Marin (1938)

Artwork description & Analysis: In this magnificent portrait of his second wife from whom he separated the previous decade, Rivera again reveals his profound artistic debt to the European painting tradition. Utilizing a device deployed by such artists as Velazquez, Manet, and Ingres—and which Rivera would himself use in his 1949 portrait of his daughter Ruth—he portrays his subject partially in reflection through his depiction of a mirror in the background. The painting’s coloration and the subject’s expressive hands call to mind another artistic hero, El Greco, while its composition and structure suggest the art of Cézanne.

Oil on canvas – Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City

The Detroit Industry Fresco Cycle (1932–33)

Artwork description & Analysis: The twenty-seven panels comprising this cycle are a tribute to Detroit’s manufacturing base and workforce of the 1930s and constitute the finest example of fresco painting in the United States. Here, Rivera takes large-scale industrial production as the subject of the work, depicting machinery with exceptional attention to detail and artistry. The overall iconography of the cycle reflects the duality concept of Aztec culture via the two sides of industry: the one beneficial to society (vaccines) and the other harmful (lethal gas). Other dichotomies recur in this work, as Rivera contrasts tradition and progress, industry and nature, and North and South America. He uses multiple allegories based on the history of the continents, as well as contemporary events to build a dramatic artwork.

Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park (1947–48)

Artwork description & Analysis: Rivera revisits the theme of Mexican history in this crowded, dynamic composition, replete with meaningful portraits, historical figures, and symbolic elements. Conceived as a festive pictorial autobiography, Rivera represents himself at the center as a child holding hands with the most celebrated of Guadalupe Posada’s creations: the skeletal figure popularly known as “Calavera Catrina.” He represents himself joining this quintessential symbol of Mexican popular culture and is shown to be protected by his wife, the painter Frida Kahlo, who holds in her hand the yin-yang symbol, the Eastern equivalent of Aztec duality.

The mural combines the artist’s own childhood experiences with the historical events and sites that took place in Mexico City’s Alameda Park, such as the crematorium for the victims of the Inquisition during the times of Cortes, the U.S. army’s encampment in the park in 1848, and the major political demonstrations of the nineteenth century. As in many previous works, Rivera juxtaposes historical events and figures, deliberately rejecting the Western tradition of linear narrative.

Diego Rivera facts

1. Rivera had a twin brother but he died at the age of two

Self-Portrait by Diego RiveraThe Firestone Self-Portrait – Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera was born on December 8, 1886 in Guanajuato, Mexico. His father Diego Rivera worked as a teacher, an editor for a newspaper, and a health inspector, while his mother Maria Barrientos de Rivera was a doctor. Diego had a twin brother named Carlos but he died less than two years after they were born.

2. He showed an inclination towards art since childhood

Diego started drawing from the age of 3. He used to draw on the walls and furniture of the house and to prevent him from doing so his parents installed chalkboards and canvas on the walls. As a child Diego was also interested in trains and machines and was nicknamed “the engineer.”

3. He was adept at several styles in painting

From the age of 10 Diego studied art at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico City. In 1902, Rivera was expelled from the academy for leading a student protest. He then traveled through Mexico drawing and painting. Teodora A. Dehesa, the governor of Veracruz, Mexico, heard about Rivera’s talent and sponsored him to go to Europe to continue his studies. In Europe, Rivera was influenced by Impressionist artists and also by Picasso’s Cubism which was on the rise during that period. Rivera’s reputation grew with time and he was considered a genius who could turn his hand to any style including Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, Cubist and Flemish.

4. Diego Rivera is one of Mexico’s greatest muralists

Diego Rivera believed that everyone should be able to view his art and hence he painted large murals (painting directly executed on the wall) on public buildings. His murals were known to depict the lives and struggles of the common man, mostly the Mexican working class and indigenous Mexicans. His first government-commissioned mural was titled Creation. It is considered one of the first important murals of the twentieth century. Along with David Alfaro Siqueiros and Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera is considered among the greatest Mexican muralists and together they are referred to as the Big Three of Mexican art.

5. Rivera was the founder of the art style Mexicanidad

Diego Rivera created his own style which focused on Mexican heritage and culture; and was marked by flattening three-dimensional elements into two-dimension and presenting objects sturdier and broader than they were in reality. This art style was called Mexicanidad and gave rise to an art movement of the same name. Orozco, Siqueiros and Kahlo all referred to themselves as Mexicanidad artists.

6. He married four women, most famously fellow Mexican artist Frida Kahlo

Rivera’s first wife was artist Angelina Beloff whom he married in 1911. He had a son with her. His second wife was model and novelist Guadalupe Marin. They married in 1922 and Rivera had two daughters with her. Rivera married Frida Kahlo in 1929 when he was 42 and she was 22. In 1955, a year after Kahlo’s death, Rivera married his agent Emma Hurtado.

7. He had a tumultuous relationship with Frida Kahlo

Diego Rivera met Frida Kahlo in 1927 when she was an art student and soon their relationship became intimate. Their marriage was tumultuous with both having multiple affairs. Frida had affairs with both men and women. Rivera even had an affair with Kahlo’s younger sister Cristina which infuriated Kahlo. They divorced in 1939 but remarried a year later. Although their second marriage was as troubled as the first, Kahlo and Rivera remained married till Kahlo’s death in 1954. Frida Kahlo became extremely famous a few decades after her death perhaps even more than Rivera.

8. Diego Rivera considered “religions to be a form of collective neurosis”

Diego Rivera was an avowed atheist. In his controversial work Dreams of a Sunday in the Alameda, Rivera depicted Mexican writer Ignacio Ramirez holding a sign which read, “God does not exist”. The work created a controversy and was not shown for 9 years till Rivera finally agreed to remove the inscription. Rivera stated: “To affirm ‘God does not exist’, I do not have to hide behind Don Ignacio Ramirez; I am an atheist and I consider religions to be a form of collective neurosis.”

9. His frescoes for the National School of Agriculture are considered his masterpiece

Between 1923 and 1926 Rivera created the frescoes in the Ministry of Education Building in Mexico City. Another famous series by Rivera are the Detroit Industry Murals. Completed between 1932 and 1933, the fresco series consists of twenty-seven panels depicting industry at the Ford Motor Company. Yet another popular work of Rivera is Man at the Crossroads which caused a controversy as it featured a portrait of Vladmir Lenin. His masterpiece is perhaps the frescoes he created for the Auditorium of the National School of Agriculture in Chapingo in 1927. The general theme of these frescoes is human biology and social development.

10. Diego Rivera is considered one of the leading artists of twentieth century

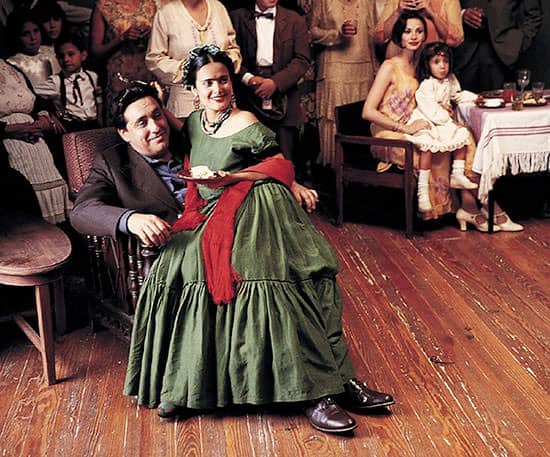

Diego Rivera died of heart failure on November 24, 1957, in Mexico City, Mexico. He is considered among the leading artists of the twentieth century. His art, though controversial in his time, is celebrated today across the world today. He is prevalent in popular culture and has been portrayed by Ruben Blades in the 1999 movie Cradle Will Rock and by Alfred Molina in the critically acclaimed 2002 film Frida.

Diego Rivera quotes

I’ve never believed in God, but I believe in Picasso.

If I ever loved a woman, the more I loved her, the more I wanted to hurt her. Frida was only the most obvious victim of this disgusting trait.

Through her paintings, she breaks all the taboos of the woman’s body and of female sexuality. (talking of his wife Frida Kahlo)

Every good composition is above all a work of abstraction. All good painters know this. But the painter cannot dispense with subjects altogether without his work suffering impoverishment.

Never before had a woman put such agonizing poetry on canvas as Frida did.

July 13, 1954 was the most tragic day of my life. I had lost my beloved Frida forever. To late now I realized that the most wonderful part of my life had been my love for Frida.

I did not know it then, but Frida had already become the most important fact in my life. And would continue to be, up to the moment she died, 27 years later.