Egon Schiele (12 June 1890 – 31 October 1918) was an Austrian painter. A protégé of Gustav Klimt, Schiele was a major figurative painter of the early 20th century. His work is noted for its intensity and its raw sexuality, and the many self-portraits the artist produced, including naked self-portraits.

The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele’s paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism.

Egon Schiele was born in Tulln on the Danube on 12 June 1890. After the great Klimt-era Egon Schiele is the painter that strongly influenced the artistic scene of Vienna in the early 20th century.

Content

Egon Schiele biography

In 1906, the young Schiele entered the class of Christian Griepenkerl, a painter of portraits and historic events at the Wiener Akademie, who was still rooted very much in the traditional disciplines. The imposed studies there, which Egon Schiele practised only reluctantly, left no significant traces in his personal artistic style. He was rather impressed by the linear, two-dimensional style of Gustav Klimt and the Vienna Secessionists, who spoke out as an artists’ group against the stiff academic conventions of the historical school and in favour of a reconciliation of art and life.

After Egon Schiele had more and more acquired the creative principles of Gustav Klimt in an act that can be described as a form of rebellion against the dogmatism of his education, his early withdrawal from the academy in 1909 accelerated his striving for his artistic self-realisation, which was independent of a painting style that celebrated the aesthetics of the beautiful appearance.

He joyfully founded the “Neukunstgruppe” and developed a drawing style that intentionally conjured up the impression of fragility and tension.

In an anti-academic and radically subjective manner, Egon Schiele chose perspectives and views in a way that figures, which are only rarely shown head-on or in full length in the picture, appear twisted and deformed by their compositional arrangement. The main motives of these decadently coloured representations are self-portraits and portraits, but also nudes that are distinguished by strongly erotic features. These pictures irritated the conventional perception and therefore became early examples of Viennese expressionism. In 1912, the artist was imprisoned for a short period of time because of his way of painting very young nude models that was thought to be immoral.

Schiele then joined the “Bund Österreichischer Künstler” and worked for the Berlin journal “Die Aktion” in 1913. In the following year he broke off his relationship with Wally Neuziel, whom he had been attached to for four years, and married Edith Harms. When Egon Schiele was a soldier for two years since 1915, he painted only very few pictures. The painter however continued to take part in very many exhibitions like the Wiener Sezessionsausstellung, which became a great success in 1918 showing 50 of his works of art.

Still in the same year Schiele died only shortly after his wife of a pandemic influenza on 31 October 1918.

Egon Schiele art

With his signature graphic style, embrace of figural distortion, and bold defiance of conventional norms of beauty, Egon Schiele was one of the leading figures of Austrian Expressionism. His portraits and self-portraits—searing explorations of their sitters’ psyches and sexuality—are among the most remarkable of the twentieth century. The artist, who was astoundingly prolific during his brief career, is famous not only for his psychologically and erotically charged oeuvre but for his intriguing biography: his licentious lifestyle marked by scandal, notoriety, and a tragically early death of influenza at age twenty-eight, three days after the death of his pregnant wife, and at a time when he was on the verge of the commercial success that had eluded him for much of his career.

Key Ideas

- Schiele’s portraits and self-portraits helped re-establish the vitality of both genres with their unprecedented level of emotional and sexual directness and use of figural distortion in place of conventional notions of beauty. Frequently depicting himself or those close to him, Schiele’s portraits often present their sitters in the nude, posed in revealing, unsettling angles—frequently viewed from above—and devoid of secondary attributes often depicted in the portrait genre. At times, Schiele used traditional motifs, giving the intensely personal images a more general, allegorical statement on the human condition.

- Creating some three thousand drawings over the course of his brief career, Schiele was both an extraordinarily prolific and unparalleled draughtsman. He regarded drawing as his primary art form, appreciating it for its immediacy of expression, and produced some of the finest examples of drawing in the twentieth century. Even his painterly oeuvre revealed a style that captured some of drawing’s essential characteristics, with its emphasis on contour, graphic mark, and linearity.

- Painter Gustav Klimt was the primary influence on Schiele’s development, serving as Schiele’s friend and mentor. While Schiele inherited Klimt’s focus on erotic images of the female form (and shared Klimt’s insatiable sexual appetite), the emotionally intense, often unsettling Expressionist idiom Schiele eventually developed, with its investigation of his sitters’ inner life and emotional states, in some ways directly opposed his mentor’s Art Nouveau–inspired style, with Klimt preferring a more brilliant palette and glimmering, patterned surfaces.

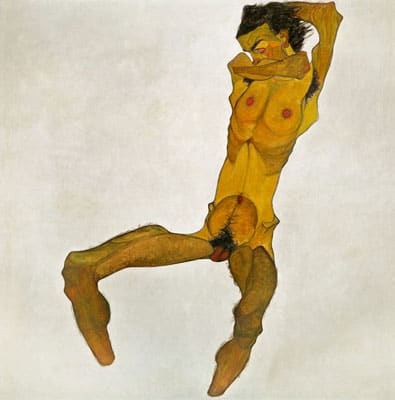

Self-Portrait (1910)

Schiele’s self-portraits are extraordinary not only for the frequency with which the artist depicted himself, but for the manner in which he did so: eroticized depictions where he often appears in the nude, in highly revealing poses—male self-portraits virtually unparalleled in the history of Western art. In this drawing, the artist has created an intense and almost frightening vision of himself: emaciated, with glowing red eyes, legs deformed and footless, his body fully exposed, yet with his face partially hidden, perhaps suggesting a sense of shame, and in a twisting pose indebted, as many writers have suggested, to the important influence of modern dance. Characteristic of the Expressionist mode that Schiele was increasingly practicing at this time, he expresses his anxiety through line and contour, and flesh that appears abraded and subjected to harsh elements.

Portrait of Gerti Schiele (1909)

Artwork description & Analysis: This is one of Schiele’s many portraits of his younger sister, Gerti, the artist’s favorite model during his early career and the member of his family with whom he was the closest. Painted when Gerti was a teenager, this early portrait demonstrates both the strong stylistic link between Schiele’s work and that of Klimt, as well as the shift away from the style of his mentor. In her pose and adornment composed from a series of flat patches with gold and silver accents, Gerti’s figure is reminiscent of Klimt’s works such as Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907). But unlike the Klimtian predecessor, the image is not so much decorative as static and soft, as if Schiele were casting his sitter in clay. In addition, Schiele replaced Klimt’s richly shimmering, gold-dominated palette with more muted colors, creating an image that appears dried-out, suggestive of decay rather than growth.

Death and the Maiden (1914–15)

Artwork description & Analysis: In this painting, one of Schiele’s most complex and haunting works, the female figure, gaunt and tattered, clings to the male figure of death, while surrounded by an equally tattered, quasi-surreal landscape. As elsewhere in his work, in this composition Schiele combines the personal and the allegorical—in this case by turning to a theme deriving from the medieval concept of the Dance of Death that reached its height in fifteenth-century German art. Death and the Maiden was painted around the time Schiele separated from his longtime lover, Wally Neuzil, and several months before he married his new lover, Edith Harms. The painting memorializes the end of his affair with Neuzil, seemingly conveying this separation as the death of true love. Interestingly enough, the manner in which Schiele’s figures are nearly consumed by their clothing and abstracted surroundings suggests the portraiture of Klimt, who likewise placed his subjects within indecipherable environments.

Hermits (1912)

Artwork description & Analysis: This rare double portrait, among the most allegorical works in Schiele’s oeuvre, shows Schiele and Klimt standing together, nearly as one. As close as the two men were, and for all their similarities, Schiele spent much of his career seeking to break free of Klimt’s influence. In Hermits, both men wear their signature long black caftans, an item of clothing for which Klimt was known, and which Schiele appropriated for his own work, perhaps in tribute. Never one for modesty, Schiele positions Klimt in the background, blind and mostly hidden, as if being consumed by the younger artist. The resulting form evokes the image of a single dark figure, indicating the confident successor Schiele assuming the mantel of the old master. The hermit motif also evokes Schiele’s existential conception of the artist as a figure existing at the margins of society.

Oil on canvas – The Leopold Museum, Vienna

Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant (1912)

Artwork description & Analysis: This is perhaps Schiele’s most celebrated self-portrait, and certainly the most storied. In this work, painted during a time in which he was participating in numerous exhibitions, Schiele gazes directly at the viewer, his expression suggesting a confidence in his artistic gifts. Although Schiele deploys less distortion than in other self-portraits, the painting refuses to idealize its subject, featuring scars and other lines characteristic of the contoured manner of the artist’s drawing style.

Exhibited in Munich in 1912 alongside work by a number of other Expressionist artists, the painting has a companion portrait depicting his lover at the time, Wally Neuzil (the Wally portrait was stolen by the Nazis from the home of a Jewish Austrian, only to be returned to Vienna in 2010 following a prolonged, twelve-year legal battle). It now serves as a “poster child” for the Leopold Museum in Vienna, which houses the largest Schiele collection in the world.

Egon Schiele facts

1. Schiele was the youngest student to ever enroll at Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts.

He was only 16 when he began at the school. After studying for three years, the artist left without graduating the Academy, dissatisfied with its conservative teachings. He and several other classmates started a collective called Neuekunstgruppe (New Art Group). Through putting on his own exhibitions, Schiele met critic and writer Arthur Roessler, who then introduced the artist to important collectors and patrons.

2. His first love was doomed.

His crush, Margarete Partonek, a girl next door in his town, was a daughter of a teacher. Although not much is known about her, supposedly his love was not totally unrequited, although he did query, “Where were you last Sunday?” in one note. Margarete kept six of his letters as well as his obituary notice, the Guardian reports. One letter reads that he would offer his “right hand to art” but “both hands” to “the loveliest girl.”

3. He wasn’t afraid of female sexual power.

Although his depictions of women may seem grotesque, they reflected only his adoration for them. In an article in the Guardian, Jonathan Jones wrote, “Schiele…is a feminist who puts women at the centre of art. He is a lover, not a hater. In his 1913 nude portrait Woman with Black Stockings, his model reclines, but not in the sidelong position chosen by male artists to depict women, seen in everything from Titian’s Venus of Urbino to Manet’s Olympia. Instead, she lies back with her legs – those stockings contrasting with bright red garters – towards Schiele, showing him her gloriously pink vagina.”

4. He was arrested on a charge of abducting and “seducing” a minor.

Schiele met his muse, Valerie (Wally) Neuzil, in 1911, and seeking inspiration they moved to Neulengbach, just west of Vienna. Coincidentally his studio became the gathering place for the town’s delinquent children, and he was subsequently accused of seducing a young girl. After spending 24 days in jail, he was released with only charges against morality. Schiele was deeply traumatized after this incident and children rarely appeared back in his work.

5. His most expensive work sold at auction is a landscape painting.

According to artnet’s Price Database, the most expensive Schiele work at auction was a 1914 landscape oil on canvas that sold for $39,821,313. The lot was sold during Sotheby’s London Impressionist & Modern Art Evening sale on June 22, 2011.

6. Four days after his marriage, Schiele was drafted into the army.

Schiele spotted Edith Harms outside his window in a Viennese suburb of Hietzing. He chose to marry Harms as she was more socially acceptable than his then mistress Wally, a model and former prostitute. He proposed a compromise to Wally, handing her a document that stated they would vacation every summer without Edith. Wally refused and they never saw each other again. In 1915, Edith and Egon married.

7. During the war, he worked on his art while guarding Russian prisoners.

Schiele’s time spent in the army was very light, he never saw any front-line fighting. He was able to paint and sketch while guarding Russian prisoners of war and performing other guard duties. By 1917, he was able to completely focus on his artistic career in Vienna. He created many works during this time, and was invited to participate in the Secession’s 49th exhibition there.

8. Schiele died when he was only 28.

In 1918, the Spanish flu spread like wildfire throughout Austria, and the local newspapers reported 2,200 deaths in a single week. His wife Edit was six months pregnant when she died, and three days later, Schiele would follow her.

Egon Schiele quotes

Art cannot be modern, art is timeless.

To restrict the artist is a crime. It is to murder germinating life.

I do not deny that I have made drawings and watercolors of an erotic nature. But they are always works of art. Are there no artists who have done erotic pictures?

-title of his earliest self-portrait…

To Confine the Artist is a Crime, It Means Murdering Unborn Life.I am so rich that I must give myself away.

-on his work…

…figures like a cloud of dust resembling this earth and seeking to grow, but forced to collapse impotently.I must see new things and investigate them. I want to taste dark water and see crackling trees and wild winds.

Everything is dead while it lives.

The picture must radiate light, the bodies have their own light which they consume to live: they burn, they are not lit from outside.

-to Franz Hauer…

At present, I am mainly observing the physical motion of mountains, water, trees and flowers. One is everywhere reminded of similar movements in the human body, of similar impulses of joy and suffering in plants…