Norman Percevel Rockwell (February 3, 1894 – November 8, 1978) was a 20th-century American painter and illustrator. His works enjoy a broad popular appeal in the United States for their reflection of American culture. Rockwell is most famous for the cover illustrations of everyday life he created for The Saturday Evening Post magazine over nearly five decades. Among the best-known of Rockwell’s works are the Willie Gillis series, Rosie the Riveter, The Problem We All Live With, Saying Grace, and the Four Freedoms series.

He also is noted for his 64-year relationship with the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), during which he produced covers for their publication Boys’ Life, calendars, and other illustrations. These works include popular images that reflect the Scout Oath and Scout Law such as The Scoutmaster, A Scout is Reverent and A Guiding Hand, among many others.

Content

Norman Rockwell biography

Norman Rockwell’s heartwarming illustrations of American life appeared on covers of the Saturday Evening Post magazine for many years. When people use the expression “as American as apple pie,” they could just as well say “as American as a Norman Rockwell painting.”

Early years

Norman Perceval Rockwell was born on February 3, 1894, in New York City, the first of Jarvis Waring Rockwell and Nancy Hill’s two sons. His father worked for a textile firm, starting as office boy and eventually moving up to manager of the New York office. His parents were very religious, and the young Rockwell sang in the church choir. Until he was about ten years old the family spent its summers at farms in the country. Rockwell recalled in his autobiography (the story of his own life) My Adventures as an Illustrator, “I have no bad memories of my summers in the country.” He believed that these summers “had a lot to do with what I painted later on.”

Rockwell enjoyed drawing at an early age and soon decided he wanted to be an artist. During his freshman year in high school, he also attended the Chase School on Saturdays to study art. Later that year he attended Chase twice a week. Halfway through his sophomore year, he quit high school and went full time to art school.

Started at bottom in art school

Rockwell enrolled first in the National Academy School and then attended the Art Students League. Because he was so serious when working on his art, he was nicknamed “The Deacon” by the other students. In his first class with a live model (a person modeling without clothing), the model was lying on her side and because all Rockwell could see were her feet and buttocks—that was all he drew. Rockwell noted that, as Donald Walton wrote in his book A Rockwell Portrait, “he started his career in figure drawing from the bottom up.”

At the Art Students League, Rockwell was strongly influenced by his teachers George Bridgeman, who helped him excel in his drawing skills, and Thomas Fogarty, who passed on his enthusiasm for illustration to Rockwell. While Rockwell was still at the school, Fogarty sent him to a publisher, where he got a job illustrating a children’s book. He next received an assignment from Boys’ Life magazine. The editor liked his work and continued to give him assignments. Eventually Rockwell was made art director of the magazine. He worked regularly on other children’s magazines as well.

“The kind of work I did seemed to be what the magazines wanted,”

he remarked in his autobiography.

Paintings made the Post

In March 1916 Rockwell traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to see George Horace Lorimer, editor of the Saturday Evening Post. It was Rockwell’s dream to do a Post cover. Since he did not have an appointment, he showed his work to the art editor, who then showed it to Lorimer. The editor accepted Rockwell’s two finished paintings for covers as well as three sketches for future covers. Rockwell’s success with the Post made him more attractive to other magazines, and he began selling paintings and drawings to Life, Judge, and Leslie’s. Also in 1916 he married Irene O’Connor, a schoolteacher.

In 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I (1914–18; a war fought between German-led Central Powers and the Allies: England, the United States, Italy, and other nations), Rockwell joined the navy and was assigned to the camp newspaper. Meanwhile, he continued painting for the Post and other publications. After the war Rockwell started doing advertising illustration, working for Jell-O, Willys cars, and Orange Crush soft drinks, among others. In 1920 he was hired to paint a picture for the Boy Scout calendar. (He would continue to provide a picture for the popular calendar for over fifty years.) During the 1920s Rockwell’s income soared. In 1929 he was divorced from his wife Irene, and in 1930 he married Mary Barstow, with whom he had three sons. In 1939 the family moved to a sixty-acre farm in Arlington, Vermont. In 1941 the Milwaukee Art Institute gave Rockwell his first one-man show in a major museum.

Wide variety of work

After President Franklin Roosevelt (1882–1945) made a speech to Congress in 1941 describing the “four essential human freedoms,” Rockwell created paintings of the four freedoms: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. He completed the paintings in six months in 1942, and they were published in the Post in 1943. The pictures became greatly popular, and many other publications asked the Post for permission to reprint them. The federal government also took the original paintings on a national tour to sell war bonds. As Ben Hibbs, editor of the Post, noted in Rockwell’s autobiography, “They were viewed by 1,222,000 people in 16 leading cities and were instrumental in selling $132,992,539 worth of bonds.”

In 1943 Rockwell’s studio burned to the ground. He lost some original paintings and drawings as well as his large collection of costumes. He and his family then settled in nearby West Arlington, Vermont. Rockwell worked on special stamps for the Postal Service as well as posters for the Treasury Department, the military, and Hollywood movies. He also did illustrations for Sears mail-order catalogs, Hallmark greeting cards, and books such as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In 1953 Rockwell and his family moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In the summer of 1959, his wife Mary suffered a heart attack and died. In 1961 he married Molly Punderson, a retired schoolteacher.

Also in 1961 Rockwell received an honorary (obtained without meeting the usual requirements) Doctor of Fine Arts degree from the University of Massachusetts as well as the Interfaith Award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews for his Post cover painting of the Golden Rule. Rockwell’s last Post cover (he did three hundred seventeen in all) appeared in December 1963. The magazine’s circulation was shrinking at that time, and new management decided to switch to a new format. Rockwell continued painting news pictures for Look and contributing to McCall’s.

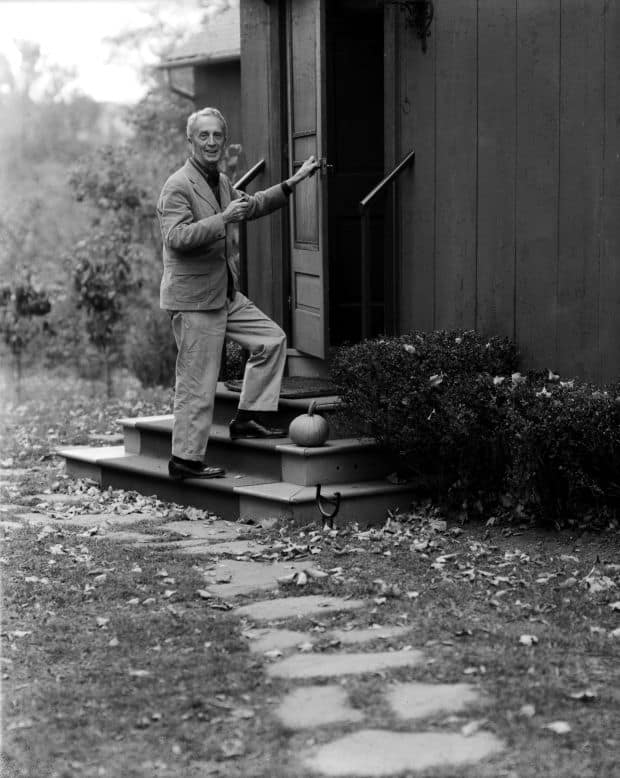

People’s choice

In 1969 Rockwell had a one-man show in New York City. Critics were usually unkind toward Rockwell’s work or ignored it completely, but the public loved his paintings, and many were purchased for prices averaging around $20,000. Thomas Buechner wrote in Life, “It is difficult for the art world to take the people’s choice very seriously.” In 1975, at the age of eighty-one, Rockwell completed his fifty-sixth Boy Scout calendar. In 1976 the city of Stockbridge celebrated a Norman Rockwell Day. On November 8, 1978, Rockwell died in his home.

In 1993 a new Rockwell museum was opened near Stockbridge. Museum director Laurie Norton Moffatt listed all of Rockwell’s works in a two-volume book; according to Landrum Bolling of the Saturday Evening Post, the total exceeded four thousand original works. In November 1999 an exhibit of Rockwell’s work entitled “Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People” opened at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia.

Norman Rockwell art

One of the most popular American artists of the past century, Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) was a keen observer of human nature and a gifted storyteller. For nearly seven decades, while history was in the making all around him, Rockwell chronicled our changing society in the small details and nuanced scenes of ordinary people in everyday life, providing a personalized interpretation—albeit often an idealized one—of American identity. His depictions offered a reassuring visual haven during a time of momentous transformation as our country evolved into a complex, modern society. Rockwell’s contributions to our visual legacy, many of them now icons of American culture, have found a permanent place in our national psyche.

The admission for this exhibition (opening March 7th) will be $15 per adult, Seniors, Florida Educators & Active Military (plus guest) $7.50, Students $5. Children 6 and under, free.

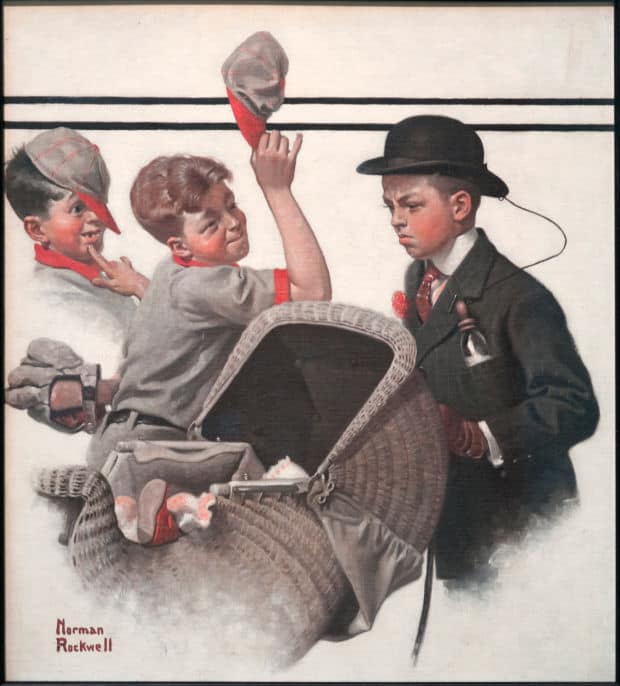

1. Boy with Baby Carriage, 1916

Norman Rockwell always wanted to be an artist. Finding success early as artist/art editor for the Boy Scouts’ Boy’s Life magazine, Rockwell was also set on becoming a cover artist for The Saturday Evening Post, which was then considered the premier showcase for an illustrator’s work. Without an appointment, the artist boarded a train to the Post’s headquarters in Philadelphia in 1916, with a portfolio containing two paintings and a sketch idea for potential covers—the editors liked what they saw, purchasing the two paintings for $75, and telling Rockwell to go ahead with his sketch idea. The artist was thrilled.

Boy with Baby Carriage was one of the paintings that landed Rockwell the job, and became his first Post cover on May 20, 1916. Painted in artist Frederic Remington’s former New Rochelle, NY studio (which Rockwell and friend/cartoonist Clyde Forysthe rented early in their careers), the humorous illustration was typical of Rockwell’s childhood-themed images of the time. Billy Paine, one of Rockwell’s favorite early models, posed for all three boys pictured in the painting, earning approximately 25 cents an hour.

Although Rockwell’s career with The Saturday Evening Post lasted nearly 50 years, resulting in 321 original covers that made him a household name, the artist never forgot his first big break from the Boy Scouts; he created yearly calendars for the Scouts throughout his entire career.

2. The Four Freedoms, 1942

Wanting to support the United States during World War II, and inspired by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s January 1941 address to Congress, Norman Rockwell sought to illustrate the President’s vision for a postwar world founded on four basic human freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Finding new ideas for paintings never came easy, but the high concept became an even greater challenge for Rockwell.

By chance, the artist attended a town meeting near his home in Arlington, VT, where one man rose among his neighbors to voice an unpopular view—that night, Rockwell awoke with the realization that presenting the freedoms from the perspective of his own hometown experiences could prove quite effective. Rockwell made some rough sketches and went to Washington to propose his poster idea, but the Ordnance Department of the U.S. Army did not have additional resources for the commission. On his way back to Vermont, Rockwell stopped at the Philadelphia office of Ben Hibbs, editor of The Saturday Evening Post, and showed him the proposed sketches for The Four Freedoms—Hibbs immediately made plans to use the illustrations in the Post.

It took several months before Rockwell even began the project, as he still struggled with how to execute the concept. Always portraying the man speaking out at the town hall meeting, Freedom of Speech started out with a much different composition; and Freedom of Worship originally was set in a barbershop with patrons of a variety of different faiths. Upon final completion of the four paintings, the artist was exhausted and doubted the concept of his Thanksgiving-themed Freedom From Want.

Running in four consecutive issues of The Saturday Evening Post, starting in February 1943, the paintings were a phenomenal success. In May of the same year, representatives from the Post and U.S. Department of the Treasury announced a joint campaign to sell war bonds and stamps—the original paintings were sent on a national tour, visited by more than a million people, who purchased $133 million worth of war bonds and stamps.

Considered part of Norman Rockwell’s most important works, The Four Freedoms continue to inspire people of all ages (Rockwell fan/art collector Steven Spielberg even recreated the image of Freedom From Fear for a scene in his 1987 movie, Empire of the Sun). Part of the permanent collection of Norman Rockwell Museum, the paintings have their own gallery created specifically for their display, inviting a space of quiet reflection for visitors.

3. The Art Critic, 1955

A popular, recurring subject in Norman Rockwell’s work are images commenting on the practice of both creating and appreciating art itself. For 1955’s Art Critic, Rockwell posed his son Jarvis, as a young artist intensely examining gallery artworks that, unbeknownst to him, are staring back at him—blurring the line of fantasy and reality.

An incredibly thorough and detailed artist, Rockwell went through dozens of sketches and drawings to figure out the composition, considering variations of Dutch portraits and landscapes for the artwork examined, before arriving on displays of a Peter Paul Rubens-inspired portrait (modeled for by his wife, Mary) and a group of Dutch cavaliers. On the student’s palette, Rockwell placed a three-dimensional dollop of paint, to remind us that we too are standing in a gallery looking at a painting.

The artist’s son, Jarvis Rockwell, went on to have a successful career as an artist in his own right, creating more abstract, contemporary artwork. Maya, a Hindu-inspired pyramid, utilizing his large collection of toy action figures, was displayed as part of a career retrospective of the artist’s work at Norman Rockwell Museum in the summer of 2013.

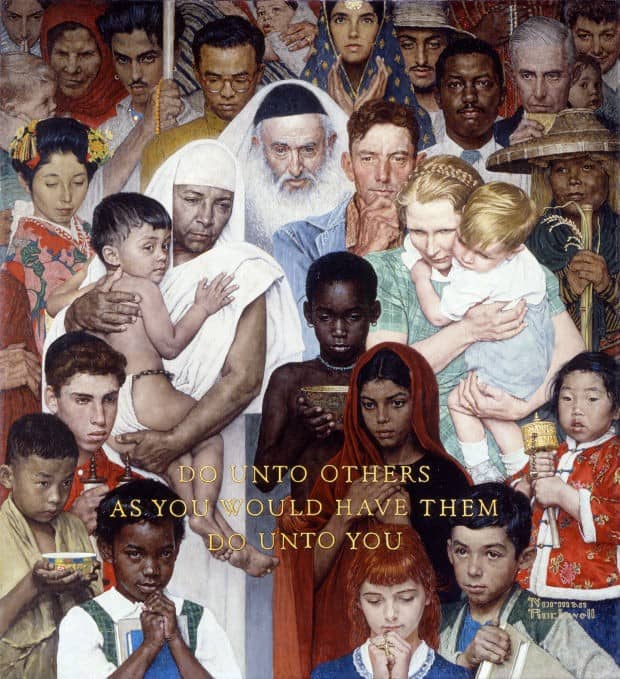

4. Golden Rule, 1961

In the 1960s, the mood in America was shifting. Once restricted from showing minorities on the cover of the Post, Norman Rockwell’s 1961 painting, Golden Rule featured a gathering of men, women, and children of different races, religions, and ethnicities, with the simple but universal phrase: “Do Unto Others as You Would Have Them Do Unto You.” In 1985, Rockwell’s iconic illustration was reimagined as a giant mosaic, and gifted to the United Nations on behalf of the United States by First Lady Nancy Reagan—it has remained on display, since that time, in the UN’s New York City Headquarters.

Coincidentally, Golden Rule began life as a drawing inspired by the UN’s humanitarian mission. Conceived in 1952 and executed in 1953, the original illustration featured 65 people representing the world’s nations, surrounding key members of the UN Security Council (USSR, UK and U.S.). The idea was to express hope in the new peacekeeping organization, and Rockwell conducted extensive research, including the photographing of the diplomats and models pictured. After completing the drawing, the artist lost faith and abandoned the project, feeling he was out of his depth. After moving to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Rockwell revisited the idea a decade later, removing the diplomats and focusing on the idea of common humanity, to create one of his most enduring portraits.

5. Home for Christmas (Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas), 1967

Norman Rockwell’s affectionate portrait of his hometown (and home of Norman Rockwell Museum) has come to symbolize the holiday season. The artist began work on the seasonal landscape painting, after moving to the New England town in the mid-1950s—pictured are his original studio (illuminated with a Christmas tree in its second floor window), town hall (which served as a backdrop for his 1955 painting, Marriage License), and the Red Lion Inn, one of the oldest inns in the country.

Working on the painting between other assignments, Rockwell finally finished the painting for McCall’s magazine in the late 1960s, perhaps explaining the transition from 1950s-era cars lining the street, to more modern automobiles entering and leaving from either side. On the far right of the painting, the viewer can see Rockwell’s South Street home, and studio, converted from an old, red carriage barn.

Living in Stockbridge for the last 25 years of his life, Rockwell once referred to Stockbridge as “the best of New England, the best of America.” In 1969, the artist lended several of his works to help preserve an old historic building, The Old Corner House (pictured on the far left of the Main Street painting)—in just a few years, thousands of appreciative fans began to visit Stockbridge to view Rockwell’s original art, and Norman Rockwell Museum was born. Moved to its current location in town in 1993, the Museum houses the world’s largest collection of artwork by Norman Rockwell, as well as his original Stockbridge studio, on a beautiful 36-acre campus, with inspiring views of the Berkshires. An added bonus: every first December the town of Stockbridge recreates the artist’s Main Street painting in time for the holidays.

Norman Rockwell facts

To millions, Norman Rockwell’s name carries the warmth of nostalgia. With humor, candor, and an incredible eye for detail, he captured small-town Americana as no artist ever had before. Born 122 years ago today, Rockwell is now embraced as arguably the most adored painter of his era.

1. HE RECEIVED HIS FIRST COMMISSION AS A TEENAGER.

Rockwell’s career got off to a meteoric start. At age 14, this Manhattan native began taking classes through the New York School of Art. Within the next year, he joined the esteemed Art Students League, an organization which also boasts such icons as Georgia O’Keeffe and Maurice Sendak as alumni. Rockwell hadn’t even turned 16 when he received his first paid commission: a set of four Christmas cards requested by a neighbor.

After that little milestone, the artist would tackle his first major assignment in 1912. At just 18, Rockwell was hired to paint a dozen illustrations for the children’s book Tell Me Why: Stories about Mother Nature by Charles H. Caudy. This $150 gig helped set up a steady job as a staff artist and eventual art director for Boys’ Life magazine, where he’d begin working before the year was out.

2. ROCKWELL’S BIGGEST INSPIRATION WAS PAINTER HOWARD PYLE.

Pyle’s sometimes known as “the father of American magazine illustration.” Appropriately, Rockwell—who became a world-famous magazine cover artist—considered him his personal “hero.” Pyle wrote and illustrated several children’s books, many of which involved swashbuckling pirates. These buccaneers utterly captivated Rockwell, who later saluted them by throwing a Pyle-esque pirate into his 1959 painting Family Tree.

3. THE U.S. NAVY TURNED HIM AWAY—AT LEAST TO BEGIN WITH.

Once the U.S. entered World War I, Rockwell tried to join the Navy, which initially rejected him on the grounds of being 17 pounds underweight. Disappointed but resolute, Rockwell bulked up by eating bananas and donuts, eventually gaining enough mass to meet the Navy’s approval. His first military assignment involved painting insignias on airplanes at an Irish base. However, after shoving off for Europe, Rockwell’s ship was diverted to South Carolina. Down in the Palmetto State, he was recruited as an illustrator for the Charleston Naval Yard’s official periodical, Afloat and Ashore.

4. IN TOTAL, ROCKWELL PRODUCED 323 COVER PAINTINGS FOR THE SATURDAY EVENING POST.

Perhaps no association between an artist and a magazine has ever been more widely celebrated than this one. Rockwell’s work first graced the publication’s cover on May 20, 1916. He’d continue to supply the Post with memorable paintings until 1963.

5. THE ARMY USED HIS FOUR FREEDOMS SERIES AS AN EFFECTIVE FUND-RAISING TOOL.

On January 6, 1941, Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave an historic State of the Union address. With the axis powers ominously looming, he held that everyone in the world deserved to enjoy freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

The president’s “four freedoms” address really struck a chord with Rockwell. Inspired, he created a quartet of paintings that portrayed these ideals in action. Today, the artist’s Four Freedoms series is one of his best-known projects. After these paintings were published in The Saturday Evening Post, the government toured the originals, enabling some 1.1 million people to view them. In the process, Rockwell’s four mini-masterpieces helped Uncle Sam sell nearly $133 million worth of war bonds.

6. THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA GAVE ROCKWELL A VERY SPECIAL THANK YOU IN 1939.

Before 3000 onlookers at Manhattan’s Waldorf Astoria hotel, BSA officials handed Rockwell a Silver Buffalo, the organization’s highest award. By that point, between his early job at Boys’ Life and his continued Post covers, Rockwell had been painting heroic scouts on canvasses for the better part of three decades. From start to finish, his professional relationship with scouting lasted 64 years—Rockwell’s last BSA-commissioned illustration, The Spirit of ’76, was finished when he was 82.

7. ALL THREE OF HIS WIVES WERE SCHOOLTEACHERS.

Norman Rockwell definitely had a type. Marriage number one was to Irene O’Connor, a boarding house instructor and occasional model for his paintings. Wed in 1916, the couple split 14 years later. Then came Mary Barstow, a grade-school teacher who had three sons with Rockwell. After her death in 1959, he settled down once more, this time with retired educator Molly Punderson.

8. ROCKWELL STRUGGLED WITH DEPRESSION.

Optimism may radiate from his paintings, but Rockwell’s days weren’t always so carefree. His second wife’s alcohol abuse problem forced the family to relocate from Arlington, Vermont to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. There, she received regular—and expensive—therapy from psychoanalyst Erik Erikson. An immigrant from Germany, Erikson also conducted numerous sessions with Rockwell, who was prone to enter states of deep depression.

9. HE RECEIVED THE PRESIDENTIAL MEDAL OF FREEDOM IN 1977.

At the ceremony, Gerald Ford praised the 83-year-old Rockwell as an “artist, illustrator, and author [whose] vivid and affectionate portraits of our country and ourselves have become a beloved part of the American tradition.”

10. THE GOLDEN RULE IS NOW ON DISPLAY AT THE UNITED NATIONS.

One of Rockwell’s most poignant paintings, 1961’s The Golden Rule, shows an international and multi-racial crowd standing in unison behind the words “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Rockwell later said that, prior to creating this piece, he’d “been reading up on comparative religion. The thing is that all major religions have the Golden Rule in common. … Not always the same words, but the same meaning.”

To celebrate the United Nations’ 40th anniversary, then-First Lady Nancy Reagan presented its Manhattan headquarters with a large mosaic version of Rockwell’s The Golden Rule. Nowadays, it’s a much-admired fixture there. “[At] virtually any hour, you will find tourists, delegates and diplomats marveling before it,” UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon says.

11. ONE OF HIS PAINTINGS VISITED THE WHITE HOUSE IN 2011.

Created for Look magazine, the main subject of The Problem We All Live With (1963) is 6-year-old Ruby Bridges. On November 14, 1960, she began attending a newly integrated elementary school in New Orleans. Given the hostile environment, U.S. Marshals were instructed to escort her.

In 1975, The Problem We All Live With became the first painting to be bought by Stockbridge’s Norman Rockwell Museum. Since then, however, it’s seen a bit of travel. Between June and October 2011, the painting was put on display in a West Wing hallway at the White House. With President Barack Obama at her side, Bridges herself was able to go and view it there.

“Every time I see it, I think about the fact that I was an innocent child that knew absolutely nothing about what was happening that day,” says Bridges, who has served as a Rockwell Museum board member.

12. STEVEN SPIELBERG AND GEORGE LUCAS ARE HUGE FANS.

Both filmmakers own impressive collections of authentic Rockwell illustrations. Apparently, there’s a bit of a friendly competition going on as well. When Spielberg learned that Lucas owned a genuine Rockwell oil painting, he decided to up the ante. “I copied [him] and got a Rockwell,” Spielberg said in 2010, “I went out and got a bigger Rockwell!”

Particularly impressive to the Star Wars creator is Rockwell’s mastery of visual narratives. “He was able to sum up the story and make you want to read the story, but actually understand who the people were, what their motives were, everything in one little frame,” Lucas said.

In July 2010, the two directors lent over 50 Rockwell paintings and sketches to the Smithsonian American Art Museum as part of a temporary exhibit called “Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg,” which ran until January 2011.

13. ONE OF HIS PAINTINGS RECENTLY SOLD FOR $46 MILLION.

Saying Grace depicts a boy and an older woman joining in prayer at a public restaurant. When Rockwell created it for The Saturday Evening Post in 1951, the job earned him $3500. Fast-forward to a December 2013 auction when an unidentified buyer shelled out $46 million to take it home. That sum more than tripled the previous highest price paid for a Rockwell—Breaking Home Ties had sold for $15 million in 2006.

14. HE’S BEEN NAMED THE OFFICIAL STATE ARTIST OF MASSACHUSETTS.

In 2008, the Bay State bestowed this posthumous honor upon Rockwell, who spent his last quarter century in the Berkshires.

15. EVERY HOLIDAY SEASON, STOCKBRIDGE RE-ENACTS AN ICONIC ROCKWELLIAN SCENE.

Rockwell once described his longtime home town as “the best of America, the best of New England.” For the record, Stockbridge loves him right back. On the first Sunday of each December, the town goes to great lengths to stage a real-life copy of his 1967 oil painting Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas (Home for Christmas). For added authenticity, antique cars that perfectly match their illustrated counterparts are brought in, and thankfully, with very few exceptions, most of the buildings look much like they did in Rockwell’s day.

Norman Rockwell quotes

Some folks think I painted Lincoln from life, but I haven’t been around that long. Not quite.

The ’20s ended in an era of extravagance, sort of like the one we’re in now. There was a big crash, but then the country picked itself up again, and we had some great years. Those were the days when American believed in itself. I was happy and proud to be painting it.

Some people have been kind enough to call me a fine artist. I’ve always called myself an illustrator. I’m not sure what the difference is. All I know is that whatever type of work I do, I try to give it my very best. Art has been my life.

No man with a conscience can just bat out illustrations. He’s got to put all his talent and feeling into them!

I just wanted to do something important. Norman Rockwell: My Adventures as an Illustrator”

I unconsciously decided that, even if it wasn’t an ideal world, it should be so and painted only the ideal aspects of it – pictures in which there are no drunken slatterns or self-centered mothers . . . only foxy grandpas who played baseball with kids and boys who fished from logs and got up circuses in the back yard.

The secret to so many artists living so long is that every painting is a new adventure. So, you see, they’re always looking ahead to something new and exciting. The secret is not to look back.

When I go to farms or little towns, I am always surprised at the discontent I find. And New York, too often, has looked across the sea toward Europe. And all of us who turn our eyes away from what we have are missing life.

Commonplaces never become tiresome. It is we who become tired when we cease to be curious and appreciative. We find that it is not a new scene which is needed, but a new viewpoint.